Agroforestry With Refugees in Uganda: Overwhelming Demand and a Huge Desire to Plant

Developing agroforestry models for refugees and host communities to meet their energy, construction and food needs.

As published on the World Agroforestry Centre blog

by Cathy Watson

“There is space for trees in refugee settlements,” Clement Okia told officials, NGOs, donors and UN agencies on 30 June 2018, as the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) closed its first agroforestry project for refugees. “Before we started, we did not realize that refugees have such a commitment to plant,” said the ICRAF country representative in Uganda.

The goal of the project was to develop agroforestry models to meet the needs of refugees and local inhabitants for tree products, particularly firewood for cooking and poles for shelter. Over 1 million South Sudanese are currently seeking refuge in Uganda, putting immense pressure on already fragile ecosystem services such as water flow and soil fertility.

Okia said that the project had clearly shown that agroforestry could be rolled out even during a humanitarian crisis and promised a second phase. “We are overwhelmed by demand.” It involved simultaneous research and actions to restore natural resources, especially the trees and shrubs that underpin the viability and resilience of refugee zones.

Funded by the Department for International Development (DFID), “Sustainable use of natural resources and energy in the refugee context” was implemented in and around Rhino Camp and Imvepi refugee settlements in the northwest district of Arua. The six-month pilot ran against the clock and weather.

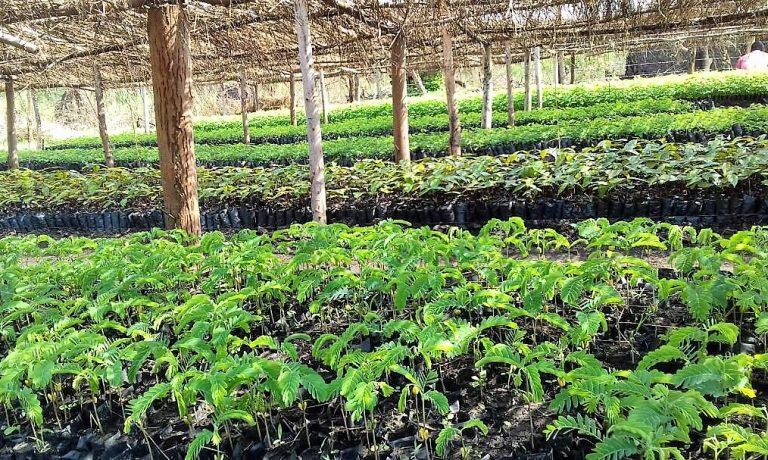

Rain only commenced in March, leaving just three months for planting. Notwithstanding, ICRAF raised and distributed 140,000 seedlings to refugees and local farmers who prepared well dug holes. The project’s 35-bed tree nursery became the main source of seedlings for NGOs working on environment and livelihoods.

Many of the young trees are now hip or even shoulder height, carefully shielded from goats and trampling by small stockades of sticks. Survival rates seem good, though more monitoring is required.

Nema Beza is growing 30 trees, among them papaya, tamarind and moringa. The 28-year-old refugee also has native species such as mahogany and Vitex doniana with its plum-like fruit. “Those trees are very important for firewood and provide protection against strong winds,” she said.

Of the 23 species raised, 85% were indigenous, and 70% of the seed was locally sourced. “We have shown that it is possible to raise indigenous species,” said Okia. “They grow well and are not on the landscape by accident. They are adapted.”

“Trees help retain water in the soil,” said Agostino Malesh, during an agroforestry training for refugees and farmers from the host community. “When it rains and there are no trees, the soil is washed away, leaving rocks, which is bad for crops. Trees also help our underground water” – a reference to groundwater recharge, a key role played by trees. Another refugee asked, “If I find land with a lot of trees, which ones do I leave?”

Participants left the meeting with pigeon pea seeds. This nitrogen-fixing shrub grows well with sorghum or maize in an easy-to-implement traditional agroforestry system that is win-win-win, increasing cereal yield, and producing protein-rich peas and, more crucially, large amounts of fuel.

Refugees have cut trees across vast swathes of land for firewood and to put up shelter. “It is a disaster,” said Gordon Eneku, an assistant environmental officer at the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in Arua. “When they came, the area was green. Today it is turning brown.”

A study by FAO and UNHCR in Bidi Bidi refugee settlement to the north concluded that all biomass would be gone in three years if radical steps were not taken to conserve and increase it. ICRAF’s own biomass study under the pilot found a similar result.

Led by ICRAF scientist Lalisa Duguma, that study was one part of the Centre’s search for evidence for a model of intervention in refugee settings where water, soil, energy and environment are integrated.

The ICRAF team also produced an inventory of trees in the mosaic landscape of farms, savannah, woodland and riverine forest. This uncovered a rich biodiversity – 81 different tree and shrub species, of which 31 had edible parts. One conclusion is that myriad species support critical dietary diversity, and interventions are needed to safeguard them.

In addition, ICRAF surveyed 280 households and found that refugees sought 32-57 trees for the plots of up to 50m x 50m that they allocated by the authorities. “It is possible to grow trees in these small spaces,” Duguma said. Nationals, who have more land than refugees, requested over 800 trees for woodlots, boundaries and orchards. “They have a massive planting opportunity.”

Finally, by meticulous counting, the researchers found 58-67 tree stumps per hectare. “There is a lot of potential to regenerate trees that have been cut,” says Duguma. The project brought in Tony Rinaudo, the leading world expert on farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR), to train local teams.

Reaction to the project has been one of relief that these issues are being tackled.

“We have been grappling with very huge numbers coming in,” said Vivian Oyella, of the Office of the Prime Minister, which is in charge of refugees. “One of the issues we always face is energy and environment. The community has been very generous, but social cohesion is broken when land is degraded. If we do not safeguard it, it will be difficult for us to host refugees.”

“Refugee settlements are part of water catchments that we need to restore,” said Callist Tindimugaya. Calling for coordination rather than “piecemeal” approaches, the Commissioner of Water Resources Management said, “How can you separate water from energy from environment?”

ICRAF’s team consists of a remarkable group of local foresters and agroforesters. Its community facilitators include South Sudanese. The initiative employed up to 60 workers during the peak potting period. Agroforestry is both knowledge- and labour-intensive and creates jobs.

The second phase of the project will include an evaluation of what worked best, scaling up of success, vast and continuous tree seedling production and planting, regeneration of root stocks, deep investment in FMNR, and developing the nursery site and seed store into a fully-fledged community learning and training centre. Already, NGOs flock to its meeting room and library.

Above all, Phase 2 will see the integration of lessons learned into humanitarian policies and approaches. What is being done here can be transferred elsewhere.

This project was part of an overall ICRAF inquiry into trees in displacement settings, including in Chad and Kenya. It was funded by DFID under a project managed by GIZ. The World Agroforestry Centre is one of the 15 members of the CGIAR, a global research partnership for a food-secure future. We thank all donors who support research in development through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund.