Bringing a Community, and Country, Together Through Art

An outdoor art exhibit in Lexington, Kentucky, has transformed the site of a former slave auction into an outdoor museum designed to unify a community.

Bringing a community, and country, together through art

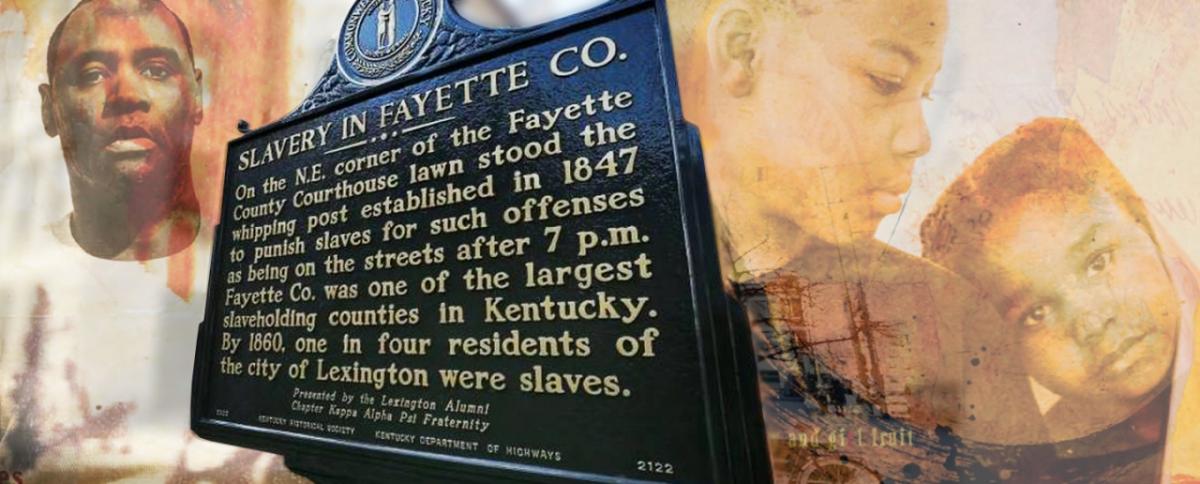

Lexington, Kentucky, was once one of the largest slave auction sites in the U.S. Today, the same site where African American men, women, and children were once sold as property is telling a different story, thanks to the civic art project “I Was Here.”

Watch the video at Wells Fargo Stories:

https://stories.wf.com/bringing-a-community-and-country-together-through-art?cid=teamm_wfs_em_img_181213_109616

Video transcript

Patrick Mitchell, photographer:

“I Was Here” means to me an opportunity to create a healing.

Marjorie Guyon, artist:

This project is 21 Ancestor Spirit Portraits that are meant to embody the people who were bought and sold in this public square. Everybody that has windows that are see-through in this square surrounding the old courthouse has wanted to be part of the project.

Bob Estes, owner, Parlay Social:

This exhibition, this sidewalk museum that we have in downtown Lexington, has opened the doors for people to talk about slavery and what happened across the street from this place in a way that provides reconciliation.

Mitchell:

A lot of times when you see pictures of black people back in the day of slavery, you think of them hanging or burning, but you forget that they were fathers and mothers, people who had souls that went to church. They fixed things. They invented things. That’s what we’ve got to get back to, is seeing each other as human beings.

John Gardner, Managing Director – Complex Manager

Wells Fargo Advisors:

To me, it’s something that’s become very personal, something that I’m proud to have been a part of, something that I’m proud of my company for supporting, and something I’m really proud of my team for endeavoring in together.

Marshall Fields, model:

If we look past the lynchings. If we look past the slavery. If we look past those crimes against humanity, the images that we see portrayed here. I’m allowed to have pride. I’m allowed to believe in myself as an individual. I’m not less than, I am an equal. But it doesn’t end with just my race, just my ethnicity. We all have the right to be respected as human beings.

Artist Marjorie Guyon collaborated with photographer Patrick J. Mitchell and poet Nikky Finney to create the project’s 21 Ancestor Spirit Portraits. Modern-day actors were asked to imagine themselves as their ancestors sold on the Cheapside slave auction block in the 19th century.

The art, displayed on Roman shades, appears in the windows of local businesses that face the old Fayette County courthouse — site of the auctions.

“I Was Here,” which debuted Oct. 11, is designed to help heal racial and other divisions within the city by focusing on the shared humanity that unites, rather than divides, people and communities.

“What we hope from this is that these Ancestor Spirit Portraits can become emblematic of a shift in humanity that begins here in Lexington, Kentucky, but travels throughout the country,” Guyon said, “and that these messages, of who we were, who we are, and who we could be are left as shadows, as kisses, as prayers for all of us in this country to begin to honor what has happened and find a way into a better future.”

Generating conversations that ‘are not always easy’

Finney, the John H. Bennett Jr. Chair in Creative Writing and Southern Letters at the University of South Carolina and author of the poem “Auction Block of Negro Weather,” portions of which appear on each Roman shade in the exhibit, said “I Was Here” is a critical acknowledgement of the horrors that took place at Cheapside.

She said the photographs, art, and poem reflect the sacrifices and contributions of the people who, as she writes in her poem, had their “family trees broken leaf by leaf then scattered by the winds of profit.”

“We wanted to use art to educate a community about history,” Finney said. “This history of the enslaved being sold in the public square of America exists not only in Lexington but across America. There are generations of certain Americans who have long whispered about these truths but never heard them echoed out loud by public officials and local governments.”

The idea for the project was born in early 2016, but it was on a cold day in January 2018 that Finney traveled to Guyon’s art studio and the dream started becoming reality. Mary Quinn Ramer, president of VisitLex, the city’s tourism office, and one of the financial contributors to “I Was Here,” was there as well.

The three talked about the racial and other divisions tearing the country apart. “We kept thinking there has got to be a different way for us to have a conversation,” Ramer said.

Shared commitment

In the early stages of development, Guyon mentioned the project to her Wells Fargo Advisors financial advisor and soon learned Wells Fargo Advisors and Wells Fargo wanted to get behind the effort.

“‘I Was Here’ fits our Vision, Values & Goals at Wells Fargo, including a shared commitment to diversity and inclusion, corporate citizenship, and team member engagement,” said Vincent Hill Sr., an advocate coach for Wells Fargo Advisors.

Ultimately, Wells Fargo Advisors and the Wells Fargo Foundation provided grants to support the project. Along with funding the creation of the art, the company sponsored a pre-launch reception, financed the creation of a brochure with locator map and detailed information about each portrait, and is supporting the effort to bring the art to other cities.

“‘I Was Here’ is a new way for all of us to see each other,” Hill said. “It’s not designed to evoke pride or guilt, but provide another vehicle for us to move forward together, and gives us another opportunity at Wells Fargo to provide courage and leadership to show the inherent humanity of us all.”

‘I knew what we were doing was right’

John Gardner, a Wells Fargo Advisors complex manager in Lexington who helped spearhead the effort to finance the project, said he’ll never forget the reaction when he and administrative assistant Syndy Deese brought the project’s creators to their office for a preview.

“Growing up in Lexington, I’ve always known the history of Cheapside,” Gardner said. “But what I really didn’t understand was how painful the scar is of that site.

“When we brought in the artists to share this project with my branch team, they went through the presentation, and it was just dead silent,” he said. “At the end, after about 20 seconds, everyone started to clap. At that moment, I knew what we were doing was right.”

‘compassionate place’

Since the art went public, Ramer said the overwhelmingly positive response has demonstrated the kind of city Lexington is, and the hearts of the people who call it home.

“‘I Was Here’ is something that really serves as a national template and a cue that can be taken for any community to finish telling the rest of the story, and in a way that allows everyone to bring their humanity to the discussion,” she said.

Bob Estes, owner of one of the local businesses displaying the shades, said the exhibit has provided a way for people to move forward.

“‘I Was Here’ has generated a lot of conversations that are not always easy between people, but opened the doors for people to talk about slavery and what happened here (in Lexington) and provide a forum for reconciliation,” said Estes, who owns Parlay Social, a restaurant and pub in Cheapside.

Like the other property owners, Estes has decided to keep the portraits up in a window of Parlay Social and his apartment above.

“They allow us to think about the past but look forward to the future,” he said, “and move forward as a country where we focus on the character of people and not where they’re from or what their color is.”

Even though the original portraits are remaining in Lexington, copies will begin traveling the state. The next stop for the exhibit is Winchester, Kentucky, in spring 2019.

“For people outside of Lexington who experience ‘I Was Here,’ my hope is that they will see the city for the compassionate place that it is,” Ramer said. “It is a very kind community, and there are a lot of people from so many different walks of life that make up this place that we call home.”