Expanding Sustainability Through Partnership

Hormel Foods joins with private and nonprofit groups to protect water quality

Inspired | Stories from Hormel Foods

By Claire Stremple

Soybeans glow in the sun on both sides of Minnesota Highway 218 through Blooming Prairie, heading north toward Minneapolis. It is a hot, dry August day, but Steve Lawler of the Mower Soil and Water Conservation District just made it rain 1 inch on the Krell family farm. On one small corner of the farm, anyway. He is demonstrating how different soil management techniques retain rainwater. If that sounds dry, it’s because the subtext is the interesting part — better rainwater retention means more nutrients stay in the soil. For farmers, that translates to better yields.

This demonstration is part of a Cedar River Watershed Partnership farm event, where a coalition of private, public and nonprofit groups addresses challenges to water resources in the Cedar River Watershed, like flooding and sedimentation. The watershed starts in southern Minnesota and extends across much of eastern Iowa, eventually joining with the Iowa River and feeding into the Mississippi River.

The partnership’s event is being held at the Krell family farm, bringing local growers together to show what a better future for farmland can look like. Justin Krell is a fifth-generation farmer. He works the land alongside his father, Rodney Krell. For a man who walks through generations of tradition every time his boots hit the earth, he’s not afraid of trying something new. “If we can change our practices and get better yields, that’s a win-win,” he says. So far, it’s working on his farm.

He watches as Lawler turns on an overhead hose to simulate rain. The sprinkler begins to douse thick slabs of sample dirt taken from different fields. Under each sample hangs two buckets, one for the water that runs off the top — taking vital nutrients with it — and another for what seeps through the soil and is absorbed into the earth. After a few minutes, water sluices into different buckets.

Justin talks about dirt the way a Silicon Valley entrepreneur with a Minnesotan accent might. The big idea he’s touting is a technique called strip tillage.

When you say “increasing yield” to farmers, their ears might perk up a bit. Those words mean dollar signs in the world of price-volatile corn. What Lawler knows is that these farmers have every reason to be conservative with their methods. You can’t just tell farmers to risk a year’s profit on a new idea, you have to show that it works. The proof is in the buckets — traditional management loses a lot of dark, soil-rich water off the top, but strip-tilled soil soaks it in.

New Math

“Ten years ago, if we wanted 200-bushel corn yield, we’d go out and apply 200 to 220 pounds of nitrogen.” Justin says that was common practice. “Now, we’re raising 240-bushel corn and we’re going out with maybe 150 pounds of nitrogen.”

Strip tillage is part of the change. The Krells use a different method of tillage than their neighbors do. The strip-till machine only disturbs the top 8 inches of soil, rather than sinking long blades deep into the ground and turning up huge clods of black dirt. Having machinery and fields that look different is a big risk in a close-knit community where many people do the same job.

But less nitrogen to produce more grain means more money in the bank. It’s thanks in part to technology that Justin is saving money and keeping his soil healthier. It’s a bonus that this kind of money-saving management means there’s less nitrogen potentially in the watersheds.

Proceeding with Excitement

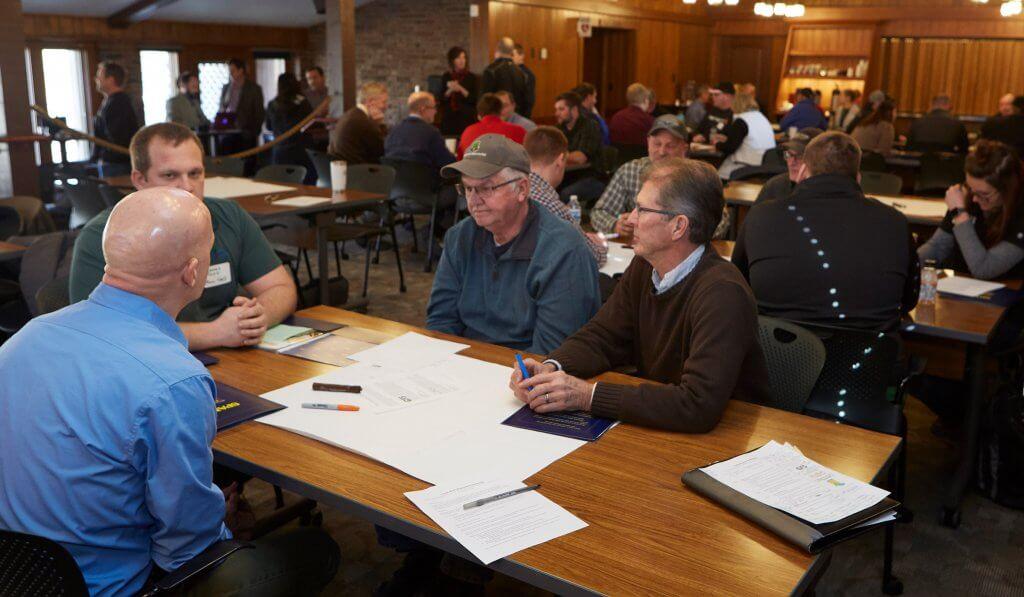

With demonstrations like this one, the Cedar River Watershed Partnership hopes to bring everyone to the table in a spirit of teamwork. The morning’s tillage demonstration is designed so that farmers can see for themselves what the tools are and how they might work. In short, they’re opening up resources for farmers and giving them opportunities to see how things work before having to make investments themselves.

They’re also offering resources. “This is a value-add to the grower — free technological assistance to help address concerns and financial assistance for change management,” says Brad Redlin with the Minnesota Agricultural Water Quality Certification Program.

Brad explains that a nongovernment group will come out to participating farms and help farmers decide on methods to increase compliance with new state water-quality rules. “We want to create space for one-on-one, site-specific solutions. How they want to do it, not how anyone is telling them to do it,” he says.

Another value of the Minnesota Agricultural Water Quality Certification Program is recognition and a 10-year contract with the state that the farm will be considered in compliance with new laws that may be passed.

For people like the Krells, farming isn’t just a livelihood, it’s a life. It’s not just how you farm that they’re talking about, it’s how you live. It’s emotional. It leads to identity and honor in a small community.

Rewarding Change

The coalition wants to get farmers certified with the state to show that they have progressive water practices. “We want to recognize growers for great work and give people certification,” Brad says.

The Krell farm has this coveted certification, and Justin says it wasn’t hard at all. He’s willing to put his reputation behind the idea, too. He tells the group, “This is a collective effort of everyone who lives in the watershed, working toward keeping the land safe, beautiful and productive for generations to come.”

The collaboration began in 2017 and is convened and managed by the Environmental Initiative, a local nonprofit. Hormel Foods is a founding member of Cedar River Watershed Partnership. “It’s right in our backyard,” says Tom Raymond, director of environmental sustainability at Hormel Foods.

What’s in it for Hormel Foods? To Tom, the answer couldn’t be more obvious. The company has already met its 2020 goal to reduce water usage by 10 percent based on 2011 levels and is working toward achieving additional reductions. This focus on conserving water in its operations and facilities also extends to producers in the Hormel Foods family, so it’s in keeping with the company’s values to help fund an initiative that encourages farmers to get certified with the state for water quality.

This is more than a move to give producers access to better practices, it’s also part of a movement to better represent farmers and give them more opportunities to share their stories.

“Thirty years ago, nearly everyone had a grandpa who was farming. As that’s changed, there’s less people with connections to agriculture,” Justin says. So, the challenge is communication between people who work the land and people who eat the bounty.

“I don’t know a single farmer who isn’t a steward of the land, because …,” Justin gestures to the lush green fields behind him, “This is our land. We live here. We live and breathe this. So, we’re not going to mistreat it. I think that’s one of the bigger misconceptions with the public.”

According to Justin, better water management is just better business. No one needs to tell a farmer that being a good steward of the land is a solid long-term economic strategy, but in a high-risk livelihood like farming, traditional methods can be hard to replace with new wisdom. “Sometimes,” he says, “You have to step up and blaze the trail.”

The Cedar River Watershed Partnership

Central Farm Service

Visit https://www.cfscoop.com/ to learn more.

Hormel Foods

Visit HormelFoods.com to learn more.

Land O’Lakes SUSTAIN

Visit https://www.landolakessustain.com/ to learn more.

Minnesota Department of Agriculture

Visit https://www.mda.state.mn.us/ to learn more.

The Mower Soil and Water Conservation District

Visit https://mowerswcd.org/ to learn more.

Environmental Initiative

A nonprofit that convenes and facilitates the partnership, visit https://environmental-initiative.org/ to learn more.