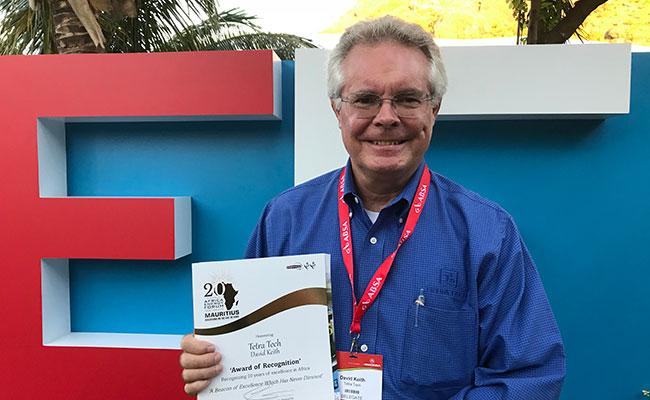

Expert Interview With David Keith, African Energy Sector Expert

Improving the sustainability of Africa’s energy sector and access to electricity for the continent’s poorest residents

David Keith is a senior vice president with Tetra Tech International Development Services. He has worked on international development engagements in the energy sectors of more than 40 countries in Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Caribbean. He has been retained as a technical expert on national energy strategy, energy sector restructuring, public-private partnerships, electricity company management, electricity tariff design, power sector planning, project financing, and industrial energy management. David has worked on energy projects in South Africa, Malawi, Uganda, Ghana, Benin, Tanzania, and for the West Africa Power Pool. He has participated in more than a dozen Africa Energy Forums (AEFs). He earned three degrees from the Georgia Institute of Technology, including a Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering.

How did you get started working in the African energy sector, and what role does the AEF play in the sector?

The first time I worked in Africa was around 1999 for the City of Johannesburg. The City of Johannesburg has city-owned power plants, utilities, markets, and even cemeteries. The project was to help the city form its public-private partnership unit to bring private partners into some of these city-owned entities, including the Kelvin power station, which was sold to AES. Our client there was Phindile Nzimandi, who years later became the CEO of the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (NERSA).

Around the same time, we won a U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) assignment to advise the formation of the West Africa Power Pool (WAPP) at ECOWAS in Abuja, Nigeria. This started us working in western Africa—Ghana, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Togo, Senegal, and other countries. For WAPP, we were tasked to develop a new model for a power pool. We had consultative sessions with WAPP member countries, utilities, and ministries, leading to an agreement that they wanted WAPP not just to promote reliability, but also—and more importantly—to stimulate investment in new generation and transmission projects. So the objective function of WAPP became to promote investment, and particularly, private investment and expansion. This led to a year-long development of an amendment to the ECOWAS treaty, the so-called Energy Protocol, which is designed to help facilitate investment.

In 2000 we won a World Bank-funded project in Uganda for the restructuring and privatization of the Uganda Electricity Board (UEB), and AEF played a key role in the project. What we had to do first was to take UEB, a vertical monopoly company, and help them unbundle into separate companies for generation, transmission, and distribution. We helped set up the regulator, the Electricity Regulatory Authority (ERA). We helped design its toolkit—tariffs, licenses, and processes. Our final role was to serve as transaction advisor for the privatization of the spin-off companies. We first got involved with AEF in the year 2000 as a way to meet potential investors for the Uganda transaction. Then in 2002 we held a formal bidder’s conference as a featured event of the AEF conference in Lyon, France. It was a separate, dedicated, formally advertised session with more than 100 people in the room to learn about Uganda. We had the Ministers of Government of Uganda introduce the sector policy; the ERA regulator explain his position; the UEB company management give their views; and the unions explain their position—that the unions actually wanted privatization. We had worked hard to get them on board. The Minister of Finance and the Minister of Energy were both up there, so it was a half-day session and quite a show. Rod Cargill, the AEF founder and organizer, was very pleased with the idea and eager to grant us the opportunity to use the forum for something that was a “real deal.”

It sounds like Uganda might have started a trend—did they?

Uganda was a turning point in the sense that it provided a real working model. The Government of Uganda was successful in marketing the distribution company and the generation company under 20-year concessions. The concession is a license to run the power companies; a lease to use the state-owned grid assets; and a financial commitment to invest in operations, maintenance, improvements, and expansion. Expanding the system was the key criterion, because when we started the project, only 5 percent of households in Uganda had electricity. The idea was to try to get it up to 20 percent by the end of the 20-year concession. That was the goal, and that was going to take quite a lot of private investment—more than $100 million in distribution alone. My understanding is that Umeme (the concessionaire) achieved these goals within 10 years. After 7 years Umeme also successfully listed itself on the stock markets of Kenya and Uganda, which provides sustainability via local ownership.

We thought it would be the first among many other countries, but that has not happened. We have been involved with the privatization of distribution companies in Nigeria, but those privatizations used a different methodology. They were not concessions but rather outright sales to Nigerian investors. The sales took many years to start but then happened very quickly, with little transparency, and so the investors did not really know what they were getting. Now they are left holding these assets, and they need some help to run them efficiently. That is where we have been called in to assist, under Power Africa. I would like to see more private sector investors in distribution in various other countries. Each will be its own case, but getting the government out of the electricity business makes sense.

What will it take to get more private sector investment in Africa’s power sector?

Certainly, there is keen private sector interest in generation, but to be a generation investor, you need to have somebody to sell the electric energy to. Generation investors want to draw a ring fence around what they are doing. They would like to come in, get some land, get the permits, and build a power station—maybe gas-fired, maybe solar, maybe wind—but their business is to build, own, and operate power stations. They have done it before in other countries, so they ought to be able to do it here in Africa. Put a ring fence around it, get a power purchase agreement (PPA), and take the PPA to lenders to obtain project financing. That’s the independent power producer (IPP) generation model. A lot of private sector players are ready to build power plants and are looking for one good customer—the so-called “creditworthy off-taker”—to be able to take a deal with a PPA to lenders for project finance. As distribution companies (DISCOs) evolve to fill this roll, we need to get them into a position of paying their bills, buying electricity, being good partners, being profitable, and being creditworthy.

What do the distribution companies need to do to become profitable?

To make the electricity company profitable we see at least two key factors, both of which may be difficult. First is fully collecting revenue from customers. Second is getting the prices right.

The biggest problem with collections in developing countries is not with the residential customers, but more with the large, institutional public-sector customers. The issue is: How do you disconnect the hospital for not paying for its electricity? How do you disconnect the water company for not paying—or the army or even the Ministry of Finance? These are the classic problems, and in some countries, the customers that I just mentioned might be 10 percent or more of the electricity.

If you cannot collect from these state entities, then you are in trouble. We have to find a way out of that box, because otherwise this will send the sector into a sort of death spiral. We call it circular debt, and we have seen an electricity debt crisis in a lot of countries. That was the case in Uganda, and we had to develop a method of getting the Ministry of Finance to solve this circular debt problem of non-payments by public sector entities. They started a system of forward-looking payments, where the entity’s budget would be tapped for advance payments that would go directly to the electric company. Then they would be settled up later, depending on how much electricity they had actually used. In another country, we helped put in a special purpose vehicle where those years of built-up debt was parked, to become due in 99 years. So that was sort of a punt, but at least that way we could clear the books and get the electricity assets sold to the private sector, which brought more than $400 million to the treasury.

How do countries go about getting the prices right?

To have a credit-worthy off-taker, in addition to collecting on all the electricity delivered, effective electricity tariffs are important. Electricity tariffs are complicated, with part of the tariff being a fixed charge, another part being for energy, and another part for power capacity—and different prices for different types of consumers connected at different voltages or in different locations. The cost of serving each customer varies widely, and so compromises must be made. Overall, the average price needs to cover the average cost, at least. The usual term for this is “cost-reflective tariffs.” If an electricity sector does not have tariffs that reflect costs, then it cannot survive. There is an amount known as the “revenue requirement” and the company needs to collect more than that to survive.

One thing I would like to talk about is the so-called “lifeline” rate. Lifeline seems like a good name, but I think it is more dangerous than it is helpful. The lifeline is the tariff for residential sector customers, wherein their first few units of energy (kilowatt hours, kWh) per month are priced at a discount, a subsidized rate. Then the price goes higher later, after they use more kWh in the month. This lifeline is really dooming the electric DISCOs in Africa, because as they connect new customers at the margin, all those sales to new customers are on the lifeline. They all are using very few units per month, and so they are all paying only the subsidized rate—a small fraction of the cost to serve them. The cost of the subsidy might be from $1 to $5 per month per customer. That might be OK if the state provided a subsidy back to the DISCO to compensate, but that rarely ever occurs, and the distribution company loses money on all these customers.

Since the company is mandated to grow the system to connect those not yet served, the problem compounds itself. The lifeline rate is something that we are stuck with that is holding back progress in Africa. Subsidies for customers might seem like a great vote-getting technique, but it ultimately hurts the electric company.

How is Power Africa working in the energy sector?

Tetra Tech is very grateful for the privilege to work as part of Power Africa the past four years. USAID has given us the opportunity to help the people of Africa, and by now we have helped a lot of people in more than a dozen countries. We have helped facilitate more than 40 deals that have reached financial close, to stimulate new generation. So far more than 2,000 megawatts (MW) have reached financial closure, with 22,000 MW more in the pipeline. In the case of distribution, we have helped a number of DISCOs in Nigeria, the transmission function of TANESCO in Tanzania, and the state utility in Liberia, and we are currently supporting the Ethiopian DISCO (EEU).

We have worked a lot in the off-grid space, which Power Africa calls “Beyond The Grid” (BTG), stimulating connections for hundreds of thousands of new customers in the poorest areas. Some of these are small-scale grids, but others are solar lanterns—a flashlight or torch that charges itself from solar energy but is smarter, with a USB port so you can charge your phone. There are far more people with phones in Africa than there are with electricity. You might notice that the kid working at the stoplight cleaning windshields in Africa has got a far more powerful device in their pocket than what anyone in the world had in the year 2005, when Umeme was awarded the concession in Uganda. Everything has changed, but most of all information and communication technology has moved ahead, and people need still more electricity. So BTG has been using these distributed generation techniques, such as mini-grids using solar energy.

The innovation of Power Africa is that its true mission is partnership with the private sector players who are investing in power plants, distribution, and off-grid. That is the whole premise of Power Africa, to go to these private sector players and ask: How can we help you? How can we help you get your deal done in whatever country you are working in? Let’s help you stimulate the market; do you need some help with a PPA? Do you need some help with the regulator or the off-taker—how can we help stimulate private investment?

Power Africa has hundreds of partners, including a lot of private sector companies, banks, and private developers. It also has partnered with governments of other countries, donors, and development finance institutions, and they meet regularly. Best of all is that there is a great leader at the helm in Andy Herscowitz, who has put his heart and soul into the mission of Power Africa. Having a dynamic person like Andy, who is a true believer and is really pushing the envelope, pushing the agenda, and getting power to the people, is so very helpful to all of Africa.

We all know we need billions of dollars in investment in Africa’s electricity sector. It used to be that foreign direct investment in electricity was led by the World Bank, but those days are gone. Long ago the private sector direct foreign investment in the industry surpassed the public-sector investment. The key here is we really believe the energy sector is just another industry—it is not a government enterprise. And if we could get that sort of belief across, then governments will get out of the power business.

As our client Emmanuel Nyirinkindi at Uganda’s Ministry of Finance told me, “I just want out of the power business. We only have 5 percent electrification. We’d have more; people can afford electricity but we have national debt and can’t get enough loans from the World Bank. Get us out of the power business, let us spend our money on healthcare and other things that people really need, education. Get the private sector in here and make them do the job.”

Where do you see Tetra Tech working in Africa in the future?

Tetra Tech’s IP3 unit had a good project some years ago that helped form the regulator in Tanzania, EWURA, which is the electricity and water utility regulatory authority. Likewise we helped ERA in Uganda. Helping regulators is a core business of ours; helping them with tariffs, helping them with licenses, and helping them with their public participation process.

As I mentioned we are helping DISCOs in Nigeria with their management, efficiency, and efforts; these types of things are another core business for us. Distribution companies and regulators are two sides of the same coin. What I can imagine is, as we go forward, we will work on different things in different countries. We will work in a number of different business areas, regulatory reform, distribution reform, off-grid, and transmission.

I believe that transmission is a new area in which we need to be getting the private sector engaged. I do not think there is a single deal yet in Africa where there has been a private power transmission line, but these are big business in India, and obviously big business in the United States. So, having transmission be done by the private sector is something we ought to be pushing for, and that was the nature of my speech at AEF back in 2013, when I chaired the session on transmission and distribution.

I expect that Tetra Tech will help provide access to finance and business and engineering advice to off-grid companies in the Solar Home System and micro-grid space. We also will support investors and funds targeting the off-grid and small-scale markets to better understand Sub-Saharan markets and dynamics, as well as provide due diligence support to justify their investments. In this way, we will continue to help the “poorest of the poor” and bring light so that kids can still read and learn after dark.