Extreme Event Attribution: What We Can Say About The Link Between Hurricane Ian and Climate Change

By: John A. Lanier

Audio File

Extreme Event Attribution: What We Can Say About The Link Between Hurricane Ian…

Let’s start with the most important aspect of this blog. When Hurricane Ian tore across central Florida, it claimed the lives of more than 100 people. Others were injured and stranded due to the flooding Ian caused. Millions of people lost power to their homes, and I am seeing property damage estimates in the range of $28-$47 billion. It was a bad storm, and it will take some time for the impacted communities to pick up the pieces.

As is often the case, moments like this bring attention to the climate crisis. As a person who cares passionately about reversing global warming, I am glad any time the issue is discussed, though I wish that we didn’t need disasters to bring it into our collective focus. That said, I find that a lot of the climate discourse after a hurricane is overly simplistic and tries to reduce the conversation to a single question - “Did climate change cause this storm?” That’s the wrong question to ask.

What Extreme Event Attributions Tell Us About Hurricanes

As an example of this, I give you the exchange between CNN anchor Don Lemon and Jamie Rhome, Acting Director of NOAA’s National Hurricane Center. Lemon asked, “What effect does climate change have on this phenomenon that is happening now, because it seems these storms are intensifying?” Rhome replied, “I don’t think you can link climate change to any one event. On the whole, on the cumulative, climate change may be making storms worse, but to link it to any one event, I would caution against that.” To be fair, Lemon didn’t directly ask if climate change caused Hurricane Ian, but you can tell that Rhome interpreted it that way. And he was quick to state, and then repeat, that you can’t link climate change to any one storm.

This all relates to the question of extreme event attribution and the studies that scientists conduct in this field. For a deep dive into this issue, I would point you to a 2016 report on NOAA’s climate.gov website, though I can explain the basics for you here. Extreme event attribution studies can “tell us whether global warming made (or will make) an event more likely than it would have been without the rise in greenhouse gasses from burning fossil fuels.” In other words, when wrestling with the impact of climate change on extreme weather events, we are talking about probabilities, not yes or no questions. I like the analogy that Dr. Marshall Shepherd at the University of Georgia uses - if a baseball player takes steroids, he is more likely to hit home runs. That doesn’t mean you can say that his 500th home run in particular was caused by his steroid use.

Attribution studies also have different confidence levels depending on the type of extreme weather event. Midway through that report is this graphic titled, “Relative Confidence in Attribution of Different Extreme Events.” If an event is further to the right on this graphic, then scientists have a better understanding of the general impacts of climate change on the weather event type. So, for instance, scientists understand very well the connections between climate change and extreme heat and cold events, but they do not understand as well the connection between climate change and tornadoes. Also, if an event is higher on the chart, then scientists are better able to detect the influence of climate change on a single event. For instance, some attribution studies are able to say how much more severe an event was because of global warming, but this isn’t always true. Again, extreme heat and cold events rank high in this metric, meaning that scientists can speak more accurately to how much worse one of those events was made by global warming.

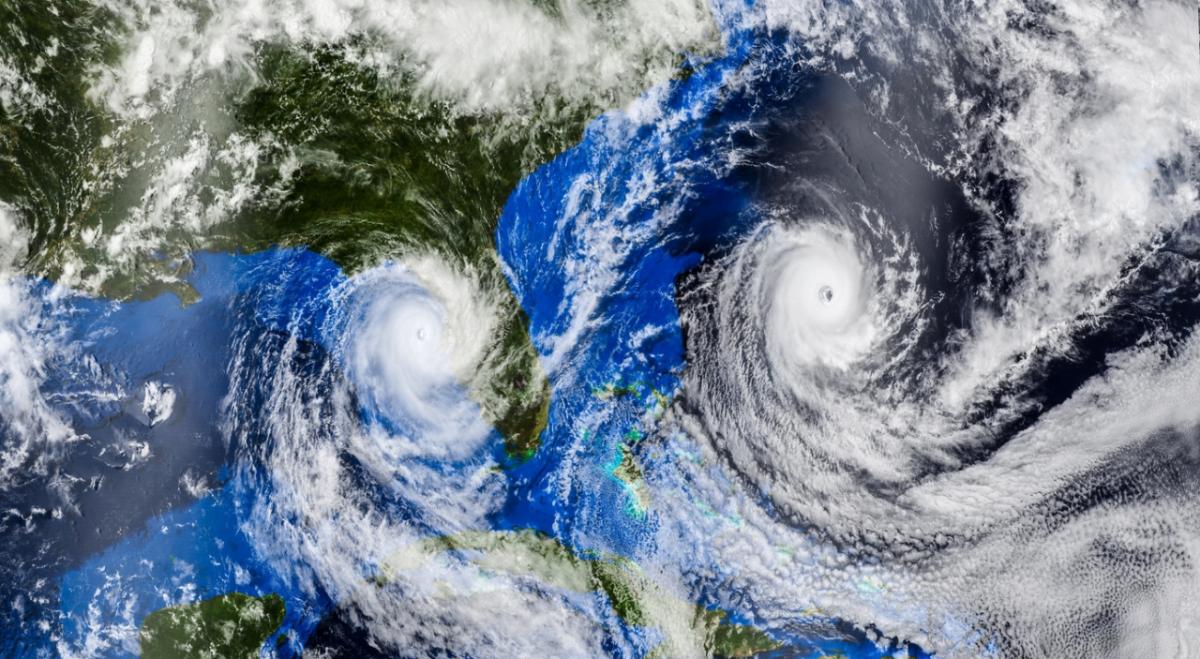

So how do hurricanes shake out? They are what scientists call tropical cyclones, and they fall relatively low on both metrics. In other words, compared to other weather event types, scientists are only able to say in more general terms that hurricanes are likely to get worse as the planet warms. That’s why Rhome was quick to say that you can’t link climate change directly to Hurricane Ian.

When It Comes to Hurricanes Getting Worse, Water Will Be the Problem

“Aha,” some climate change deniers might say. “There is no link between global warming and hurricanes!” Well, not so fast. There is a clear link - it’s just that it’s less specific than for other weather event types. Forecasting hurricanes is already hard, and it’s harder to then layer on how global warming would alter those forecasts. As Rhome correctly, stated, “On the whole, on the cumulative, climate change may be making storms worse.” So let’s unpack that a bit. What does the scientific community know about the connection between climate and hurricanes? And what does it mean for the future?

Here is NASA’s take on the connection between climate and hurricanes. Scientists know that global warming is raising sea levels, and so they also know that storm surges and flooding from hurricanes is getting worse. They are also confident that climate change will result in hurricanes with heavier rainfall. That’s because a hotter planet has more evaporation, meaning more water vapor is in the air for a hurricane to latch onto and send downward as rainfall. They also believe, albeit with less confidence than rainfall impacts, that the increase in warmer waters and water vapor in the atmosphere will make storms stronger in terms of maximum and sustained wind speed. They continue to study, but don’t yet have firm conclusions, on the impact of climate change on the speed with which hurricanes move, how big they get, and where they will tend to go. Also, it does not seem that hurricanes that make landfall in the United States are becoming more frequent in our warmer world, at least at this time.

What does all of that mean for the future? Well, it tells me that water is going to be a bigger and bigger problem for hurricanes going forward. At least one attribution study has already come out that suggests climate change increased Hurricane Ian’s rainfall by 10%. And because scientists have good projections about sea level rise caused by global warming, they can make predictions about how much worse hurricane flooding will be. Back in July, NPR wrote an in-depth article about projections for Miami, New York, and Washington DC in particular. Take a look at the graphics in that article, and you’ll see just how much worse flooding in these cities is expected to get. And I expect one more thing as a result of more and more water in hurricane-struck areas - insurance markets will fail. As NPR recently covered, that could already be happening in Florida, in part because of how much insurance litigation takes place in that state. Regardless, it’s easy to imagine that insurance companies might simply stop offering insurance on homes and businesses that are at risk of hurricane flooding. The implications of that are staggering for the future of such communities.

So at the end of the day, it’s not appropriate to say that climate change caused Hurricane Ian. It is, however, more than appropriate to say that climate change will make future storms like it worse, especially when it comes to extreme rainfall and flooding. That will mean more lives lost, more lives displaced, and more economic damage going forward.

Ecocentricity is available weekly via email subscription. Click here to subscribe.

Ecocentricity Blog - Is Patagonia the Rabbit of the Duck: Why It's Okay to Answer "Both"

Ecocentricity Blog: Unpacking the Latest Heat Wave in the West

Ecocentricity Blog: Shifting the Burden of Proof: Why It's Now on the Fossil Fuel Industry to Defend Itself