General Mills Works to Decouple Emissions from Business Growth

by Mary Mazzoni

Originally published on TriplePundit

Agriculture accounts for around 9 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The global tally of agricultural emissions is even higher, with estimates ranging from 13 to 24 percent of total GHGs.

Meanwhile, “Climate change is becoming a source of significant additional risks for agriculture and food systems,” according to a 2015 report from the World Bank. The international finance institution predicts that shifting average growing conditions and increased climate and weather variability will present increasing risk to farmers and food companies in the coming decades.

As our warming climate poses greater and greater uncertainty for the food sector, leading companies are looking to shrink their own contributions to climate change and build resilience for the days to come.

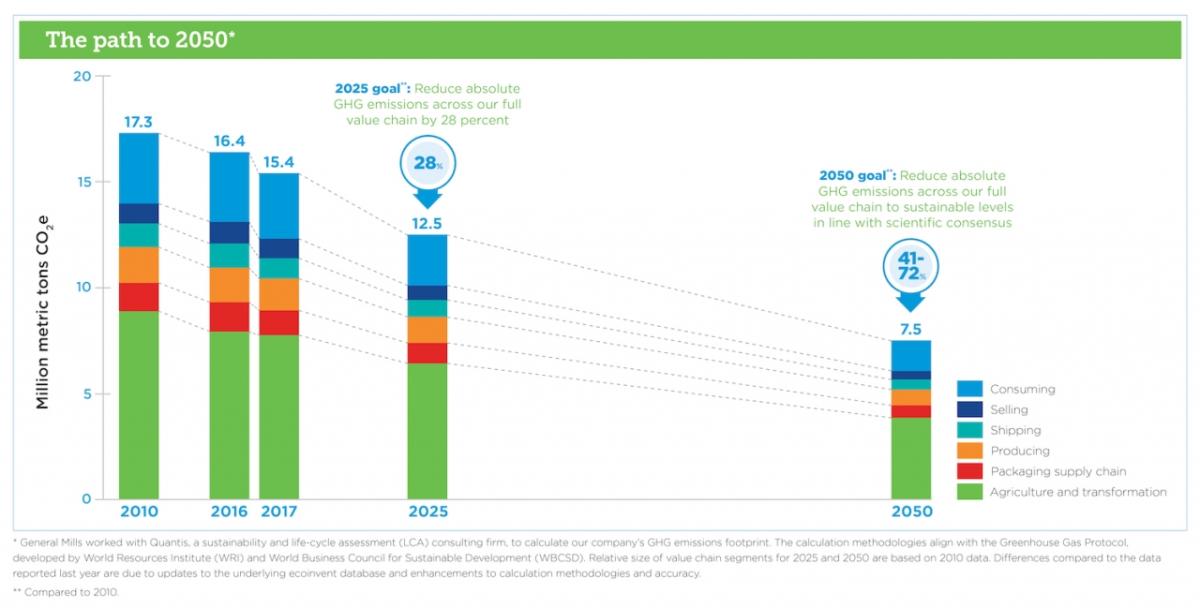

Case in point: Global packaged foods company General Mills committed to a set of science-based emissions targets ahead of the COP21 climate talks in 2015, where world leaders drafted the landmark Paris Climate Agreement. The company was among the first to have its plan approved by the Science-Based Targets Initiative—indicating its goal to reduce value chain emissions by 28 percent by 2025 aligns with the global effort to limit temperature rise to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius.

In its 2018 Global Responsibility Report, released earlier this year, the company behind brands like Cheerios, Yoplait and Häagen-Dazs announced it’s making serious progress toward its GHG goals. Its greenhouse gas emissions footprint dropped by 11 percent in 2017, compared to a 2010 baseline, while the business grew by 6 percent over the same time period.

“It’s exciting to know that we’ve been able to grow our business from 2010 while reducing our impact on an absolute basis,” Jeff Hanratty, applied sustainability manager for General Mills, told TriplePundit. “When you set a goal like this, using science-based tools, you’re establishing what Mother Nature needs of your company—not necessarily what the company can accomplish. It’s promising to see that we’ve been able to move against that.”

We sat down with Hanratty to find out how General Mills managed to make such a significant dent in its footprint and learn more about the global food giant’s future plans as it seeks to continue growing the business while further reducing emissions.

Cutting costs, shrinking footprints

While naysayers often dismiss corporate sustainability as an unnecessary expense, many of General Mills’ GHG-reduction initiatives actually helped the company save money. “The main successes we’ve had along the way so far have been where we found cost savings,” Hanratty explained.

Energy efficiency and reduction projects, for example, helped General Mills save $2 million in the last fiscal year while avoiding nearly 15,000 metric tons of carbon-equivalent emissions.

In June 2017, General Mills signed a 15-year virtual power purchase agreement for 100 megawatts of the Cactus Flats wind project in Concho County, Texas. It will produce “the equivalent of up to a third of our electric consumption in the U.S.,” Hanratty said.

Still, Hanratty and his team know these cost-saving measures will run dry eventually—and likely far before General Mills reaches its goal to slash value chain emissions by 28 percent by 2025. Further moves will require the company to think outside the box, especially as it looks to expand while reducing emissions.

“Decoupling business growth and GHG emissions is a challenge,” Hanratty told us. “We’re not going to be able to achieve our ambition by just working on the things that have been successful in the past, such as energy efficiency in our manufacturing plants. We’re going to have to find it somewhere else.”

Looking to the future: Investing in sustainable agriculture

As General Mills looks toward 2025, its team identified sustainable agriculture as a key lever to drive down emissions across the value chain.

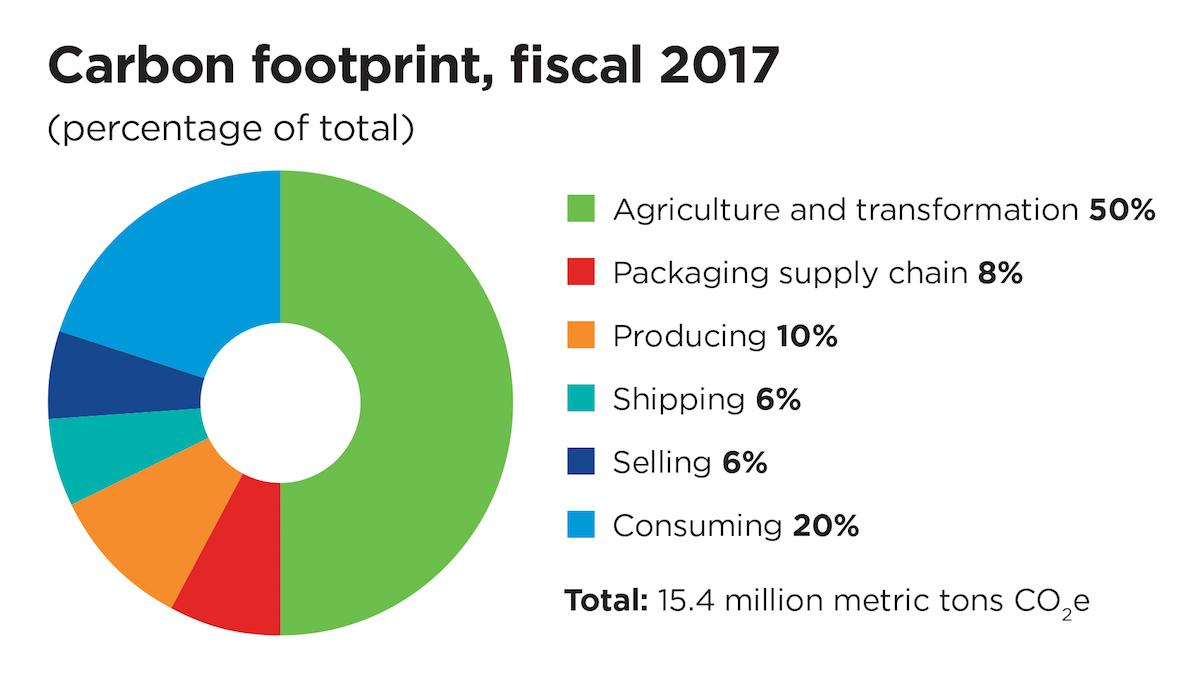

Such a move makes sense considering that growing and transporting crops and transforming them into food ingredients accounts for half of the company’s value chain emissions. “The ingredients themselves are half of our footprint,” Hanratty explained. “We have to mine that area for greenhouse gas reduction.”

To that end, General Mills has invested more than $3.25 million in soil health initiatives across the U.S. Its investments support on-farm research through supplier and grower partnerships such as the Soil Health Partnership and the Midwest Row Crop Collaborative. “We see [these investments] as a benefit for society and for agriculture, but there is also a huge potential to capture carbon in agriculture—which can help us with our science-based target,” Hanratty said.

Leading on commitment: Value chain reporting in the food sector

Experts consistently predict that the food sector will be among the first to experience disruptive impacts from climate change, and General Mills was one of the first companies to publicly attribute profit loss to our warming climate.

In a 2014 quarterly report, the company told investors it lost 62 days of production due to the extreme winter—a hit that impacted its production . The fact that the company is already seeing business suffer at the hand of weather extremes played a role in its decision to lead on climate action, Hanratty said.

“We see our climate change ambition and our activities around both climate change and water risk as a business resiliency play,” he told us. “We feel that we need to act because we could be affected the soonest. But we’ve realized since making these commitments that, because we’re closest to the earth, we have a greater opportunity to act. Because we’re buying food directly from the land, in agriculture particularly, we have an opportunity to cause change and use our scale for good—and that’s what we’re in the process of doing.”

Unlike most of its peers, General Mills reports on full value chain emissions—from farm to fork. Many top companies report only their direct emissions (Scope 1) and those from the generation of purchased electricity (Scope 2). But for several industries, including food products and agriculture, indirect supply chain emissions (Scope 3) account for the lion’s share of a company’s footprint.

“Our manufacturing footprint is 10 percent of our overall footprint,” Hanratty said. “If we need to reduce our emissions by 28 percent, we could eliminate our entire manufacturing operation and we wouldn’t reach that goal, so we knew that we had to go elsewhere.”

Though value chain emissions assessment and mitigation is still a fairly nascent process, General Mills hopes its early success will attract attention from fellow food companies and their suppliers. “Our ambition is about getting better and bringing others along to do the same,” Hanratty said. “Now, some of our competitors, suppliers and customers also have science-based targets that span the value chain.”

The bottom line

Cutting emissions while growing the business is a huge achievement for any company, but we’ll need the private sector to do far more if we hope to cap global temperature rise at 2 degrees Celsius—which climate scientists deem essential if we are to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

By themselves, national commitments associated with the Paris Agreement will only limit warming to 3.5 degrees Celsius this century, as Oscar-nominated filmmaker Josh Fox pointed out in a 2016 op-ed on TriplePundit, and business engagement is needed to fill the gap. For its part, General Mills isn’t pretending the process will be easy.

“We wanted to be leaders in this space, and it’s scary,” Hanratty admitted. “We’re feeling a little better because we’ve had some success and we have some ideas. But again, our plan is to grow the business and any growth we have, we have to abate.”

While the home stretch will be undoubtedly challenging, the company remains optimistic that it can lead its industry toward climate leadership. “We’re on trajectory toward 2025,” Hanratty concluded. “We’re very positive that it’s achievable.”