How Well Do You Know Your Incentive Programs?

Clever energy storage financing could boost your general fund

How Well Do You Know Your Incentive Programs?

If your K-12 school district or community college could reduce energy costs and steer those savings to educational improvements, wouldn’t you jump at the chance? California’s Grossmont Union, Poway Unified, Mountain View Los Altos and Visalia Unified are just a few of the districts that have tapped into energy storage to shrink their electrical bills. They are now serving as beacons to others.

The key to their savings lies in the fact that by installing battery-based energy storage on their campuses, schools can mitigate the effect of demand charges, which can account for as much as half the monthly electricity bill. Demand charges are fees for spikes in power drawn from the grid, due to fluctuations in demand, such as increased AC use on hot days, or reduced generation from solar panels due to passing clouds. The energy storage system automatically senses the fluctuation in the load and discharges power from the batteries to meet the demand, preventing that spike at the meter.

The savings you may have overlooked

So, energy storage can indirectly help fund education initiatives through a reduction in energy costs. What’s less well known is the direct impact that energy storage can have on educational funding. Thanks to a significant political will to promote energy storage installation, the State of California allows Prop. 39 and 51 funds, as well as general obligation (G.O.) bonds, to be used to finance behind-the-meter energy storage projects. Not only that, but these funds can be converted to unrestricted general funds.

More important for cash-strapped schools is that some of these funds can be made available almost as soon as the energy storage system is installed, thanks to California’s Self-Generation Incentive Program (SGIP). Available to ratepayers of PG&E, CSE (SDG&E), SCE or SoCal Gas, SGIP is a financial incentive program that promotes the installation of certain new technologies (among them solar PV and energy storage) that are deployed to meet all or a portion of a facility’s electricity needs.

How it works

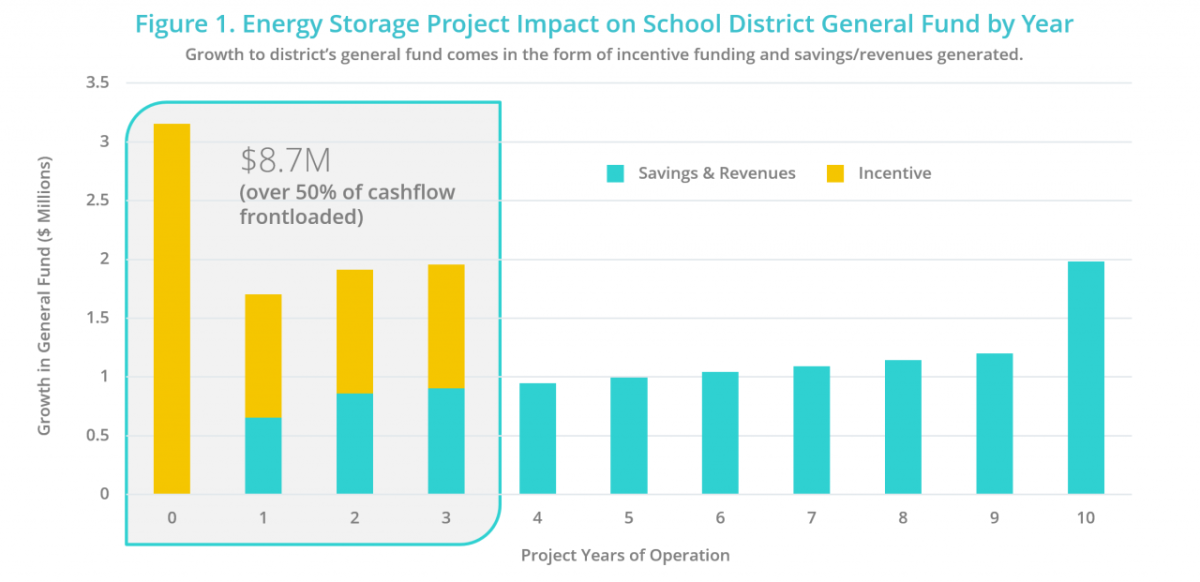

As an example, consider a scenario in which a school district uses $10.3 million of G.O. bond funding to purchase an energy storage system, which has an operating lifespan of 10 years. Because the district owns the system, it can claim all of the SGIP incentive. It receives 50 percent of the incentive when the utility gives permission to operate the energy storage system, with the remainder paid over the first three years of operation. As Figure 1 illustrates, the SGIP funds, combined with the savings and/or revenues generated by the storage system total $8.7 million for those first three years.

Savings and revenue continue to accrue for the next seven years, totaling $15.2 million by the end of the system’s lifespan.

Converted to general funds, all these funds can enable schools to commit to much-needed infrastructural improvements, hire additional teachers, or fund traditionally cash-strapped arts programs.

Don’t miss out, storage experts can help

While Prop. 39 funding is coming to a close, $3 billion in Prop. 51 funding for the modernization of school facilities can be applied to energy storage projects. If you have remaining funds, or if you want to apply for new funding, now is the time to act and maximize the dollars that can be channeled into your district’s general fund.

At this point, you may be wondering what school district facility manager has the time or resources for this type of initiative. The truth is, few go it alone. As the school districts mentioned above can attest, it makes sense to work with a full-service energy storage partner that has extensive experience in the education sector. The partner can help apply for incentives, manage the engineering, permitting and installation processes, and operate the energy storage systems to achieve high savings-to-investment ratios.