Mastercard: How This Entrepreneur Is Bringing Indigenous Fashion to Main Street

By Sarah Levitsky

As Chelsee Pettit kneeled on the floor, a bottle of Windex in one hand, a fistful of paper towels in the other, she knew one thing for certain: She had made it.

Pettit, founder of the Indigenous clothing brand Aaniin, was mopping the floors of her 6,500-square-foot pop-up at Toronto’s Eaton Centre — supported by Mastercard, it was billed as the first 100% Indigenous-owned department store in Canada — while her team rang up tens of thousands of dollars in sales. “Holy cow, this is actually working,” she recalled thinking at the time. “It was working because I was letting my team do what they needed to, making money in the space.”

Pettit’s entrepreneurial journey didn’t begin with a clear path or a traditional business plan. It wasn’t until she saw a man wearing a T-shirt with an Indigenous symbol that she felt an immediate sense of connection. Excited to learn more, Pettit, who is Anishinaabe and a member of Aamjiwnaang First Nation, approached him — only to discover the symbol was not Indigenous at all, but simply a triangle.

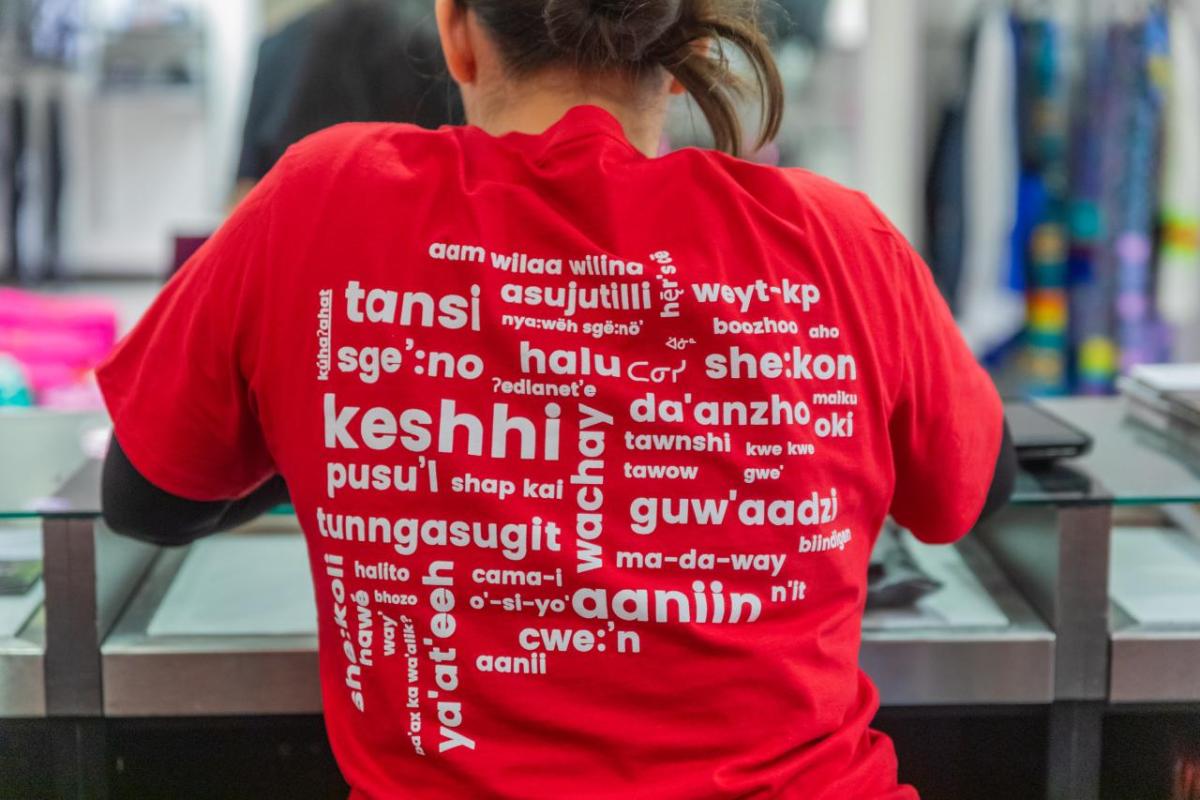

But this disappointment quickly turned to inspiration. “That’s when I decided to create something real,” she recalls, leading her to launch Aaniin, a brand that tells stories and connects wearers to Indigenous culture through meaningful design via QR codes on the apparel.

Aaniin, which means “hello” in Ojibwe, quickly grew into a successful venture. In 2022, Pettit was recognized as one of the inaugural recipients of the Mastercard x Pier Five Small Business Fund, helping to propel Aaniin’s growth. Today, Aaniin is a true reflection of Pettit’s vision for inclusivity, community and collaboration. The Mastercard Newsroom sat down with Pettit to learn more about her entrepreneurial journey, the lessons she’s learned and what’s next for Aaniin.

What was your journey as an entrepreneur, and how did you develop the skills that led you to start your business?

Pettit: I dropped out of three college programs before the age of 21. I just wasn’t having a lot of success with traditional schooling. The whole trajectory of going to school, getting a corporate job and then working to buy a house — it wasn’t for me. So, I decided that when I turned 18, I would drop out and get a job working at LensCrafters and Pearle Vision in the mentor department. It was the first time I was able to learn a skill and put it into practice. I was amazing at it. Within a few weeks, I was one of the best salespeople at that store. At 18, not knowing what I was doing with my life, working in retail was such a blessing. It gave me confidence and made me realize that I do have a lot of knowledge to offer — just not in traditional ways.

Three years later, I had another business idea called Intuition Business Solutions. I wanted to create a space for Indigenous representation in business consulting, not just for Indigenous businesses but for small businesses in general. I’d offer services like marketing or website redesigns for free to coffee shops, which I knew couldn’t afford them. I was still working as a store manager, so I filled my extra hours with learning new skills, like business registration. I designed logos, built websites and helped small business owners who didn’t know how to navigate these tasks.

The vision for that business idea ultimately led me to what Aaniin is today. I wanted to create an inclusive workplace where people could learn valuable skills without needing a formal education. My goal was to build an ecosystem where businesses could collaborate and support each other.

As an Indigenous female entrepreneur, what are some of the challenges you face in the business world, and how have you navigated them?

Pettit: As Indigenous people, we face many barriers — cultural appropriation, access to capital and the assumption that we should donate all our profits because we're seen as part of a communal, socialist economy. People often think that I donate all proceeds to Indigenous charities, which is crazy. We’re a for-profit business trying to impact the Indigenous economy, and we can't do that if we donate all of our profits.

I also knew people would place higher expectations on me as an Indigenous business owner. With manufacturing, I started this business with a $300 credit card bill. I didn’t have thousands of dollars to launch a clothing brand or hire a graphic designer. I spent every minute of my time trying to grow the brand for free because I didn’t have resources.

I think many people severely overestimate what it takes to start an Indigenous business. They don’t understand how small businesses are built in general, and they expect us to operate at a much higher standard. For example, people think we should be weaving fabrics in our backyards. I’ve had many people at markets ask if I made the T-shirts myself. I tell them, ‘No, it's a T-shirt. There are suppliers and manufacturers for a reason — they’ve figured out how to do it. I don’t need to reinvent the wheel.’

How did you approach making your brand more accessible and inclusive for a wider audience?

Pettit: When I announced that I was starting my business, my mom, who’s Belgian and Dutch, immediately asked, ‘Can I wear this T-shirt?’ I told her, of course, it’s just a T-shirt, not regalia. She asked, ‘What if I don’t know how to pronounce it or remember what it says?’ I said, ‘Indigenous people who don’t speak the language won’t know how to pronounce it either, or what it says.’

That’s when I decided to bridge the educational gap. I wanted to take the pressure off the wearer, so they wouldn't feel stressed about being asked what the T-shirt says. I added QR codes to all of our garments and accessories. Each design links to our translation page, where customers can see the meaning behind the designs.

You were an inaugural recipient of the Mastercard x Pier Five Small Business Fund in 2022. What motivated you to apply and how did it impact Aaniin’s success?

Pettit: At that time, I didn’t know where to start, had no money and was selling garments every day after work. I’d go out to market on weekends and sell the whole time. It was like that for about two and a half months, and I made $15,000, which was great, but there was no profit because I didn’t have proper manufacturing processes and was doing everything for free. The garments were expensive, too.

Receiving that grant was a huge boost for the business. I remember filling out the application — it was a personal experience. They weren’t asking typical grant questions like, "What will you do with the money?" or "What’s your secret sauce?" Mastercard really wanted to understand what was going on with the business. The questions felt personalized, and it seemed like they genuinely cared about the businesses, our personalities and our missions … It was the first time I was really able to step back and think big picture. As a business owner, you’re always focused on the now, so it was nice to reflect on the future.

You just finished up your four-week pop-up at the Eaton Centre in Toronto. How does it feel to break new ground in such a significant way?

Pettit: At the pop-up, nothing has changed from when I started four years ago. I was still doing everything alone, reaching out to the Eaton Centre with no money. It was a scary thing to do, but delusion was the only thing that gave me the confidence to keep moving forward. As an entrepreneur, you just get better at utilizing resources and finding faster and bigger ways to do things.

Zooming out a bit, what role do you believe small businesses play in shaping communities and driving economic growth in general?

Pettit: A huge role. Take, for example, the fact that we saw almost every single customer we ever had come back to our pop-up in the Eaton Centre. People are looking for community. People enjoyed the staff smiling, engaging with them and sharing stories about all the businesses. Our staff was called storytellers, not sales associates, because we weren't just selling products. We were sharing the meaning and purpose behind the Indigenous brands in the store. I love focusing on product knowledge and storytelling — it's one of my best skills.

This was one of the biggest things to prove that people want in-store experiences. They don't want cookie-cutter retail or big-box store displays. We added personal touches to everything — merchandising, marketing and every product in the store had personality behind it. That's something I think is severely lacking in other retailers in the mall.

Looking to the future, what are your goals for Aaniin? How do you plan to grow your brand and continue to impact the Indigenous business landscape?

Pettit: For the first time, I’m able to invest in others more than I invest in myself. Investing in my employees is massive. I’ve been doing this alone for four years, so this is the first year I have a small team to support me. Looking ahead, we might be able to do three pop-ups next holiday season, or the one after that. I’m not focused on hard timelines; I want to prioritize the quality of what we execute moving forward.