The New Role of the 21st Century Architect and Designer: Health Professional

by Drs. Stephanie Timm and Whitney Austin Gray

Almost half of all U.S. adults suffer from one or more chronic health condition that has the potential to be prevented through changes in behavior and environment.1

Architects affect health

In the U.S., human health is largely determined by five key factors: social/economic environment, physical environment, behavior, genetics and access to healthcare.2,3 Although access to healthcare is often considered one of the smallest health determinants,3 a disproportionate 86% of our national health spending is directed toward treating chronic diseases that are generally preventable.4

New efforts to re-prioritize healthcare spending focus on changes in our environment and behavior. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention claims that “approaches that change the environment reach more people, are more cost efficient and are more likely to have a lasting effect on population health.”5 Heart disease (the leading cause of death in the United States), for example, may be prevented through physical activity, which can be supported by active furnishings (such as treadmill desks) and interior/exterior design that promotes walking and stair use (such as aesthetically pleasing staircases).6–9

In short, architects play a critical role in the future of public health. The key question therefore is, are architects prepared for this responsibility?

Preparing to design for health

The building industry is by no means blind to the rapidly growing need and desire for healthy design. Deloitte’s 2017 Innovations Report, for instance, highlights occupant health and well-being as one of the top five emerging themes in commercial real estate.10 Demand for building professionals with the knowledge and expertise to design for health is therefore likely to grow rapidly over the next decade.

New resources and certifications are emerging to help building professionals learn more about the intersection of health and building design. For instance, over 2,100 people in more than 50 countries have earned the International WELL Building Institute’s WELL Accredited Professional (AP) credential. This credential – obtained through a rigorous examination administered by the Green Business Certification Inc. (GBCI) – signifies knowledge in human health and well-being and the built environment, as well as a specialization in the WELL Building Standard.

Mara Baum from HOK found that gaining the WELL AP credential has been crucial for distinguishing her as a leader in this emerging field. “I’ve been engaged in design for health and well-being for many years, but until the advent of the WELL AP credential, there was no clear and easy way to convey this focus. The WELL AP sends the message to my clients and colleagues that I am trained to implement WELL on our projects.”

Human Resources professionals are emerging as key allies

Architects have long been aware that their knowledge and ability to design well are not always sufficient to reach peak building performance. Most building elements are dynamic and contingent upon a host of variables that change over time, which require an integrated approach to design and operations. Even the best designed office gyms, for example, may lie dormant without campaigns to promote active engagement of the management and the workforce.

Just as facility managers emerged as crucial players in maintaining building energy efficiency goals, it is becoming apparent that a new professional must champion long-term maintenance of healthy building goals.

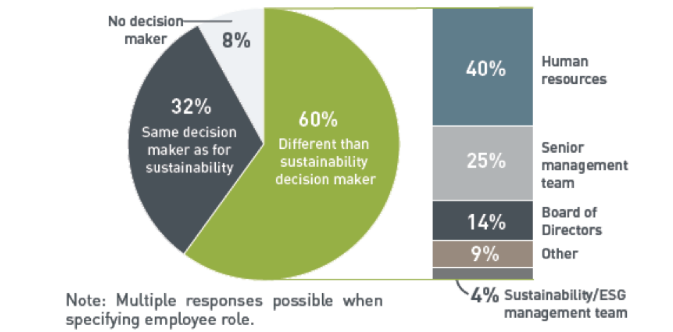

In commercial and industrial buildings, HR professionals are emerging as key allies for architects to work with in healthy design. The Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark’s (GRESB) 2016 Health and Well-being survey found that 40% of the companies who have delegated health responsibility to someone other than their sustainability manager have chosen someone from HR, thus indicating a potential new emphasis for HR professionals.11

The efficacy of healthy design will likely depend upon how well architects prepare for, and how well they collaborate and strategize with those helping to facilitate everyday design performance. Lida Lewis, Director of Well-being Design for HKS, agrees, saying “The WELL system moves beyond build-out to forging a stronger, longer term relationship with our clients into operations. We’re very interested in having HR at the design table, and they will find strong allies for their own goals, and new tools to help achieve them, with those who hold a WELL AP credential.”

Architects can learn more about the WELL Building Standard at www.wellcertified.com and learn more about becoming a WELL AP at www.wellcertified.com/well-ap.

References:

1 Ward BW, Schiller JS, Goodman RA. Multiple Chronic Conditions Among US Adults: A 2012 Update. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:130389. doi:10.5888/pcd11.130389.

2 Health Affairs. Health Policy Brief: The Relative Contribution of Multiple Determinants to Health Outcomes. 2014. doi:10.1377/hpb2014.17.

3 Booske BC, Athens JK, Kindig DA, Park H, Remington PL. Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health.; 2010. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/differentPerspectivesForAssigningWeightsToDeterminantsOfHealth.pdf.

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/. Published 2016.

5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Four Domains of Chronic Disease Prevention.; 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/pdf/four-domains-factsheet-2015.pdf.

6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart Disease Prevention With Healthy Living Habits. https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/healthy_living.htm. Published 2015. Accessed March 2, 2017.

7 National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015 with Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville; 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2017.

8 Boutelle KN, Jeffery RW, Murray DM, Schmitz MK. Using signs, artwork, and music to promote stair use in a public building. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):2004-2006. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11726383. Accessed April 5, 2017.

9 MacEwen BT, MacDonald DJ, Burr JF. A systematic review of standing and treadmill desks in the workplace. Prev Med (Baltim). 2015;70:50-58. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.11.011.

10 Deloitte. Innovations in Commercial Real Estate | Preparing for the City of the Future.; 2016. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/real-estate/articles/commercial-real-estate-industry-outlook.html. Accessed December 8, 2016.

11 GRESB Real Estate. Health and Well-Being Module.; 2016. https://gresb.com/.