New Wave of Social Entrepreneurs Tackling Complex Issues

The term “social entrepreneur” is being tossed around so often that I’m beginning to fear it will become as meaningless as “green.”

A true entrepreneur looks a lot like Mark Zuckerberg or Sam Walton. He (or she) is willing to risk the loss of capital in an effort to make money. He is an innovator, a dreamer perhaps, who’s not afraid to try new things. But unlike Zuckerberg and Walton, a social entrepreneur is driven first by the need to create social impact. A financial return is, in other words, the means to the end – what’s necessary to sustain the social impact.

Why all the sudden interest? Because the old ways – traditional charity, corporate check writing and government programs simply aren’t working. Today’s challenges require new thinking and new models. At the same time, employees and other stakeholders are demanding that the products and companies they support share their values and engage people in meaningful ways. Social entrepreneurism is even fueling renewed interest in MBA programs as students increasingly search for work that’s purposeful and focused on more than just profits, Net Impact reports.

Amid all the noise, the picture of a true social entrepreneur is emerging. The Schwab Foundation describes these leaders as having:

· An unwavering belief in the innate capacity of all people to contribute meaningfully to economic and social development

· A driving passion to make that happen

· A practical but innovative stance to a social problem, often using market principles and forces

· A zeal to measure and monitor their impact

· A healthy impatience

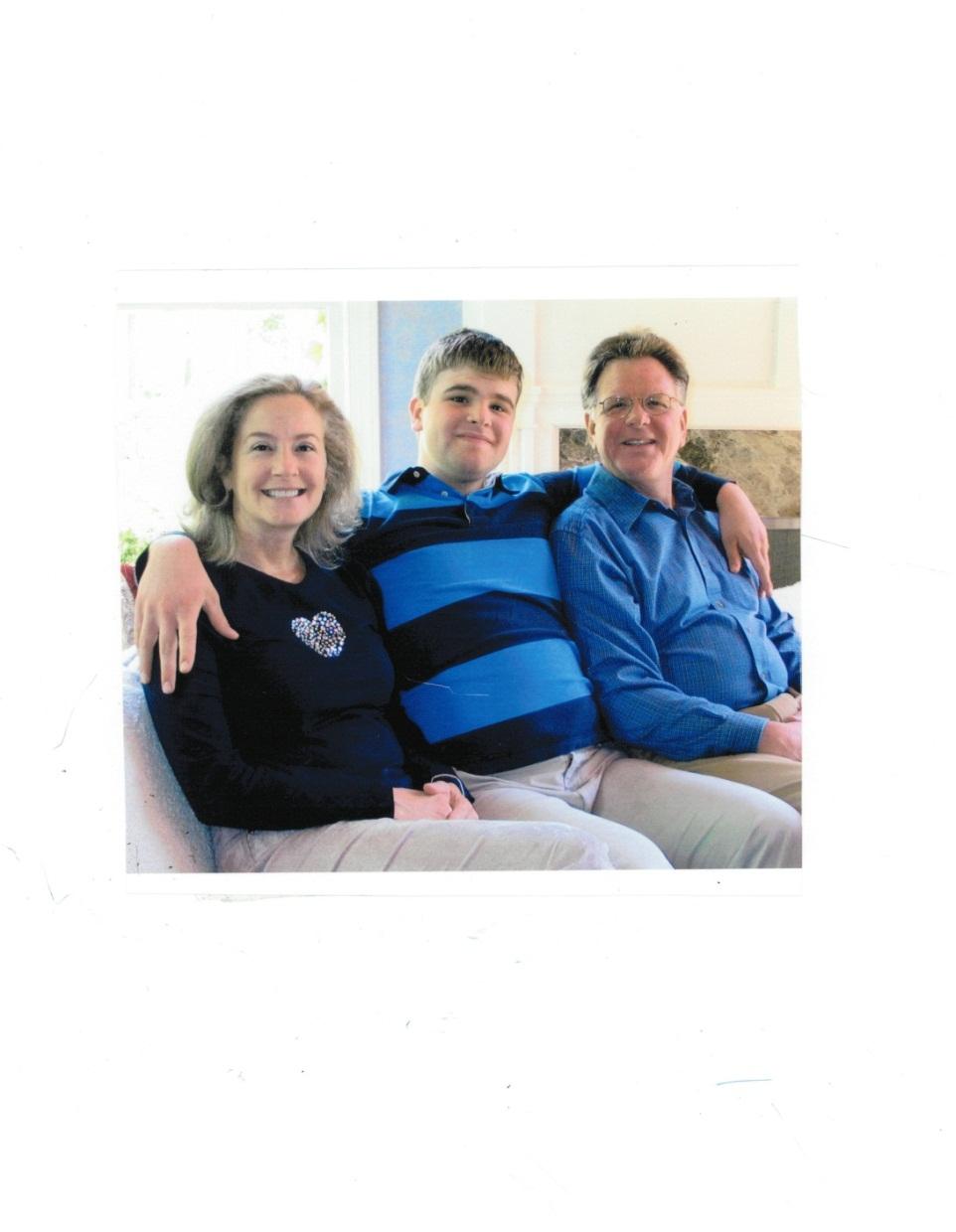

As a leader in CSR and Cause – our agency purpose is, after all, telling stories that matter – we’ve been fortunate to work with some of these social entrepreneurs. Our client Gregg Ireland of Chapel Hill, NC is a great example of this. Gregg, a successful investment manager, founded Extraordinary Ventures in 2007 to create self-sustaining businesses that could employ young adults with autism.

Like many parents of a child with autism, Gregg and his wife Lori watched their 23-year-old son Vinnie “age out” of the school system and enter an uncertain world that is too often marked by waiting lists, unemployment and isolation. Over the next decade, the ranks of these young adults with autism will swell to 500,000. Without work or school, they face the loss of skills, behavior problems and in some cases, institutions.

To avoid that, Extraordinary Ventures has developed five different business ventures that employ 40 young adults with autism or developmental disabilities. The ventures include transit bus detailing, laundry, candle and soap making, office services and a meeting and event center.

Fourteen other “model” programs – most started by other parents/social entrepreneurs – have been identified by Autism Speaks through a grant from the Ireland Family Foundation. The founders of those programs will join the Irelands and about 150 others in Chapel Hill next week for a first-of-its-kind summit to help grow the social entrepreneurial movement.

A big part of the program will be sharing lessons learned – and there are many.

The Irelands say they made a lot of mistakes in their first attempts to build businesses around the skills of their son and other young adults with autism. To start with, they relied too much on a traditional non-profit approach and staff. Success came when they turned to new business school graduates who had the entrepreneurial talent, energy and creativity they needed.

Other Extraordinary Ventures lessons that can be applied to social enterprises include:

1. Just get started. A large infusion of capital is not necessary – start small

2. Experiment. Not every idea will work. Don’t be afraid of trial and error

3. Focus. Identify the societal and market need you can help fill and stay focused on it

4. Create ambassadors for your purpose, from investors who believe to passionate supporters

Sheila Gruber McLean co-leads MSLGROUP’s PurPle (Purpose + People) practice in North America. She is the mother of a 16-year-old son with autism.