The Potential of Agroforestry to Enhance Land Degradation Neutrality: Case Study From Tanzania

Researchers highlight how the ngitili agroforestry system aids land restoration, in a new publication for the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification

By Ruth Ogendi

Since the adoption of the 2030 Agenda in 2015, the Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) target-setting programme encourages countries to conserve, sustainably manage and restore land.

Judith Nzyoka of the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and colleagues explain in a chapter of a new book — A better world: actions and commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals: life on land — how agroforestry can support countries achieve LDN using a case study from Tanzania.

LDN is a state whereby the amount and quality of land resources necessary to support ecosystem functions and services and enhance food security remains stable or increases within specified temporal and spatial scales and ecosystems. With agricultural land being severely affected by degradation, net primary productivity continues to decline as the human population and demand for food and goods grows. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimated in 2015 that land degradation worldwide costs USD 6.3–10.6 trillion annually.

“For agroforestry to meet the LDN targets, appropriate incentives based on the role of trees in the supply of ecosystem services are necessary to motivate farmers and landowners (who play a key role in restoration) to favour agroforestry as a valuable option for increasing the productivity and profitability of their lands, including risk-mitigation mechanisms that attract more investment in agroforestry,” said Nzyoka.

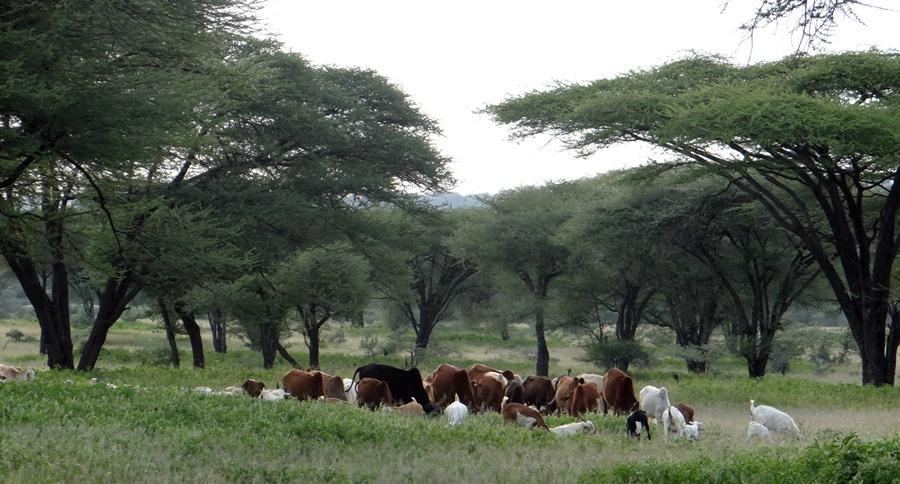

A traditional system in Tanzania provides a close example of what Nyzoka means. Known as ‘ngitili’, it is a dry-season fodder reserve developed by the Wasukuma people of Shinyanga. Ngitili is an enclosure system where farmers conserve or plant trees in grazing land that then provide livestock feed and wood for energy and construction. The ngitili area remains closed to livestock at the beginning of the wet season but is opened for grazing at the peak of the dry. Hence, the system alleviates dry season fodder shortages, preventing environmental degradation, such as soil erosion, and helps conserve biodiversity.

Village environmental committees and local leaders determine the levels of harvest for different users. The village government (‘dagashida’) and community policing (‘sungusungu’) ensure the decision is properly implemented. The communities have rules and regulations on how much of the products are to be harvested, by whom and under what circumstances. This is a strong indicator to avoid overharvesting, which later affects the sustainability of the system.

The ngitili system ensures fair and equitable sharing of the benefits among group members engaged in managing parcels of land, as such adhering to the principles of LDN. Often the benefits go to public infrastructure, such as schools and roads, and any remaining funds are shared among the members.

Initially, around 611 hectares of such schemes existed but the number grew significantly to more than 378,000 hectares by 2005. The system blended with other agroforestry practices, such as woodlots, becoming instrumental in rangeland management and forest restoration in 833 villages.

The Shinyanga region has undergone several processes in terms of land-use characteristics and associated practices. In the period before the 1930s, the landscapes in the region were considered sustainably managed but became intensely degraded between the 1930s and 1980s.

The degradation created huge social and ecological problems requiring restoration measures. One such effort, the Shinyanga Soil Conservation initiative (best known by its Swahili acronym HASHI (Hifadhi Ardhi Shinyanga)) that the Tanzanian government devised, relied on ngitili. HASHI received considerable political support at national level, with the government making several policy provisions, such as revisions of land-tenure policies and mobilization of financial resources, to support restoration. Although HASHI officially closed in 2004, the activities continued under the Natural Forest Resources and Agroforestry Management Centre and through community members.

The empowering approaches of HASHI, combined with the adoption of traditional knowledge of ngitili management, enabled agropastoralism to meet restoration goals. Ngitili also demonstrated that rural resource users play a key role in restoration and, as such, necessitate appropriate incentives. The individual areas restored may not be large but the number of people who individually or jointly own ngitili is great and spread widely over the region, transforming once-degraded areas.

Read the chapter

Nzyoka J, Minang PA, Ogendi R, Duguma L. 2018. The potential of agroforestry to enhance Land Degradation Neutrality. In: Nicklin S, ed. A better world: actions and commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals: life on land. Vol 4. Leicester, UK: Tudor Rose. pp 69–72.

About The World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF)

The World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) is a centre of scientific excellence that harnesses the benefits of trees for people and the environment. Knowledge produced by ICRAF enables governments, development agencies and farmers to utilize the power of trees to make farming and livelihoods more environmentally, socially and economically sustainable at multiple scales. ICRAF is one of the 15 members of the CGIAR, a global research partnership for a food-secure future. We thank all donors who support research in development through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund.