Quileute Tribe Uses the Forest for Ancient Traditions

Forestry companies and Native American tribes are deeply intertwined in Washington state, where they must work together to share and sustain the resources the land provides. The humble Quileute Tribe of La Push shares how the forest is the lifeblood of their rich history.

Walking through the forest several years ago, Rayonier forester Blake McMichael stopped when he heard a strange sound under his cork boot.

Looking down, he immediately realized he was face-to-face with history: it was an ancient Native American spearhead. Within hours, the priceless relic was with the Quileute Tribe, our neighbors in La Push. After thousands of years, a piece of their past was returned to them.

The spearhead, made from obsidian rock that does not exist in this part of the United States, tells the story of a tribe that once roamed the entire west coast. They numbered in the tens of thousands, traveling all the way from the glaciers of what is now Washington state to the coastal rainforests. They lived on salmon and other fishes, large game, seals and whales.

Today, the tribe’s reservation covers one square mile off the coast of northern Washington. While their community is now much smaller, the Quileute are deeply dedicated to their heritage. They work with their neighbors in order to continue traditions that date so far back, there is no way to calculate just how old they are. In their own words “we’ve been here since time immemorial.”

Like many of Washington’s tribes, the Quileute often work with neighboring forestry companies to access the resources they need.

“Rayonier is the largest private landowner in our treaty area,” says the tribe’s natural resources director, Frank Geyer. “They have been very good about listening to the tribe and understanding our needs, and we also try to understand theirs. It’s always been stressed by the Tribal Council that relationships are of utmost importance to us.”

Ensuring the Quileute Tribe has Access to the Resources it Needs

Longtime Rayonier forest engineer Mike Leavitt, a lifetime resident of Forks, has spent his career working with the Quileute.

“I’m proud of the relationship we’ve garnered over the years with the tribe,” he says. “It’s a very warm and friendly partnership that we have.”

The tribe calls on Mike when there is a need for wood materials for a carving or a traditional salmon bake; when it’s time to forage for the plants used to make Labrador Tea; or to obtain cedar bark that will be used in traditional weaving.

We’ve worked together on projects to improve the forest ecosystem and to study the wildlife that lives within it.

Restoring miles of fish habitats together

And Mike has called on the tribe for support in our efforts to restore upland streams in Rayonier forests. The projects, a part of Washington’s Forests & Fish program, help bring back salmon populations that haven’t been seen in the waters, sometimes, for more than a century.

In one particular case, the tribe secured grant funding to replace two perched culverts (undersized pipes) with a large bridge on a private Rayonier road. That project successfully opened a critical 7 ½-mile area for salmon spawning and rearing.

“Fish really are the lifeblood of any tribe in the northwest,” Frank explains. “So the forests—and the streams within them—are of vital importance to the tribes.”

Cedar Bark Peeling for Traditional Weaving

During a special time each spring when the sap of the cedar trees makes them just right for peeling, the Quileute tribe travels to cedar forests to engage in their timeless bark peeling tradition. Mike helps the tribe find the best location to source the material for a year of weaving projects.

It’s a special celebration in which several generations take part, gathering together in the same forest. To collect the bark, they cut a flap near the bottom of the tree, then walk backward while holding on to it, peeling a long strip of bark off the tree. The outer bark then has to be removed, leaving the thin cambium layer. Cedar is stored for a year to dry properly prior to using for weaving. That material then has to be soaked in hot water and finally made into strips the tribe can use to weave traditional baskets, clothing and other items that are tied to Quileute ceremonies and traditions.

“This is my history. It’s what we’re doing to preserve what has been done in the hands of many different weavers for generations,” says Cathy Salazar, a weaver descended from master basket makers.

Each basket is unique, with intricate designs that speak to the Quileute tribe’s history, such as birds, canoes and seals.

Cathy says her first basket took a year to make. Now, 24 years later, she can make one in three hours. Cathy gives most of them away as gifts. She also shares her gift of weaving, assisting beginning weavers.

The Red Lizard Petroglyph: A One of a Kind Discovery

The Quileute lost many of their most cherished artifacts in a tragic fire in the 1800s. So when something from their rich past is discovered, like the spearhead, it is true cause for celebration.

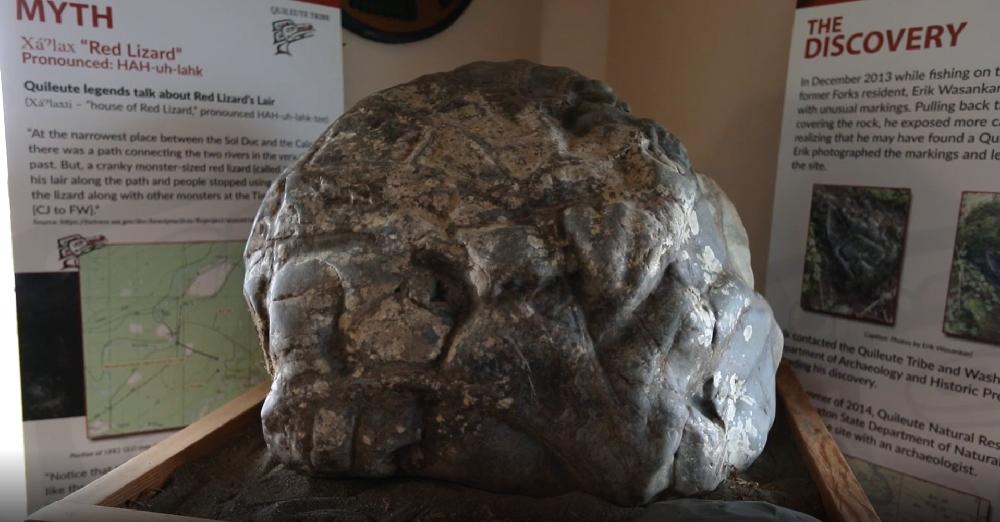

We all celebrated when a fisherman found the Red Lizard Rock on the bank of the muddy Calawah River. The priceless boulder, carved before Europeans arrived in America, illustrates one of the oldest stories of the Quileute history:

K’wati, a powerful Quileute patriarch, used his tongue to slay a monster-sized red lizard. The monster had blocked the shortest path between the Sol Duc and Calawah rivers. K’wati’s victory over it opened the passage for the tribe.

To protect, preserve and display the massive rock, the Quileute needed to move it to a safe indoor location in La Push. The tribe, archaeologists, the Department of Natural Resources and our team joined together for a special ceremony at the river celebrating the discovery. Then we helped move it out of the river, across our forests and onto the Quileute reservation.

“The best part of our history is the stories. Stories were always told by the old people in wintertime around the fire,” says Rio Jamie, a member of the tribal council. “It’s fitting that Red Lizard Rock is now here in our elder center.”

For the Generations To Come

We’ve been neighbors with the Quileute for nearly 100 years here in Forks. Our job is to protect and maintain sustainable forests for generations to come. That gives us a common goal that we share with our neighbors who look far into the past and the future.

“It’s my job to manage the resources of this tribe in the best manner that we can to ensure those resources are there for what we call the next 7 generations,” explains Frank, the Quileute Natural Resources Manager. “It’s not just about today. Knowing that motivates me to be there for the Quileute people.”

Perhaps 100 years from now, the tribe and Rayonier will be sharing the stories of this generation and how it ensured the forests of western Washington would continue to provide for us all.

To learn more about our work with Indigenous Peoples, click here.