Rain or Shine: Resilience Needs a Little More Attention

Are water utilities doing the right things to drive toward resilience?

It's been said that Texas suffers perennial drought, broken up by severe floods from time to time. These days, however, Texas isn't alone in its misery.

Researchers from Climate Central analyzed 65 years of rainfall records in the United States and found that 40 of the lower 48 states have seen an increase in heavy downpours since 1950. We're talking about the kind of flood-making torrential events that exceed the top 1 percent of all rain and snow days. And droughts are frequent, too. During the second half of 2012, more than half of the land area in the United States suffered from a drought ranked moderate or worse.

Download the full 2019 Water Report

Both floods and droughts impact water systems, and water providers are squarely focused on hardening their systems to withstand these natural events, as well as manmade threats. Are water utilities doing the right things to drive toward resilience? Results from Black & Veatch's 2019 Strategic Directions: Water Report survey indicate that most are on the right track, although there is room for improvement. Overall, water utilities would benefit from taking more proactive action toward resilience and being more ambitious in chasing funds to pay for projects.

"Weather" or Not

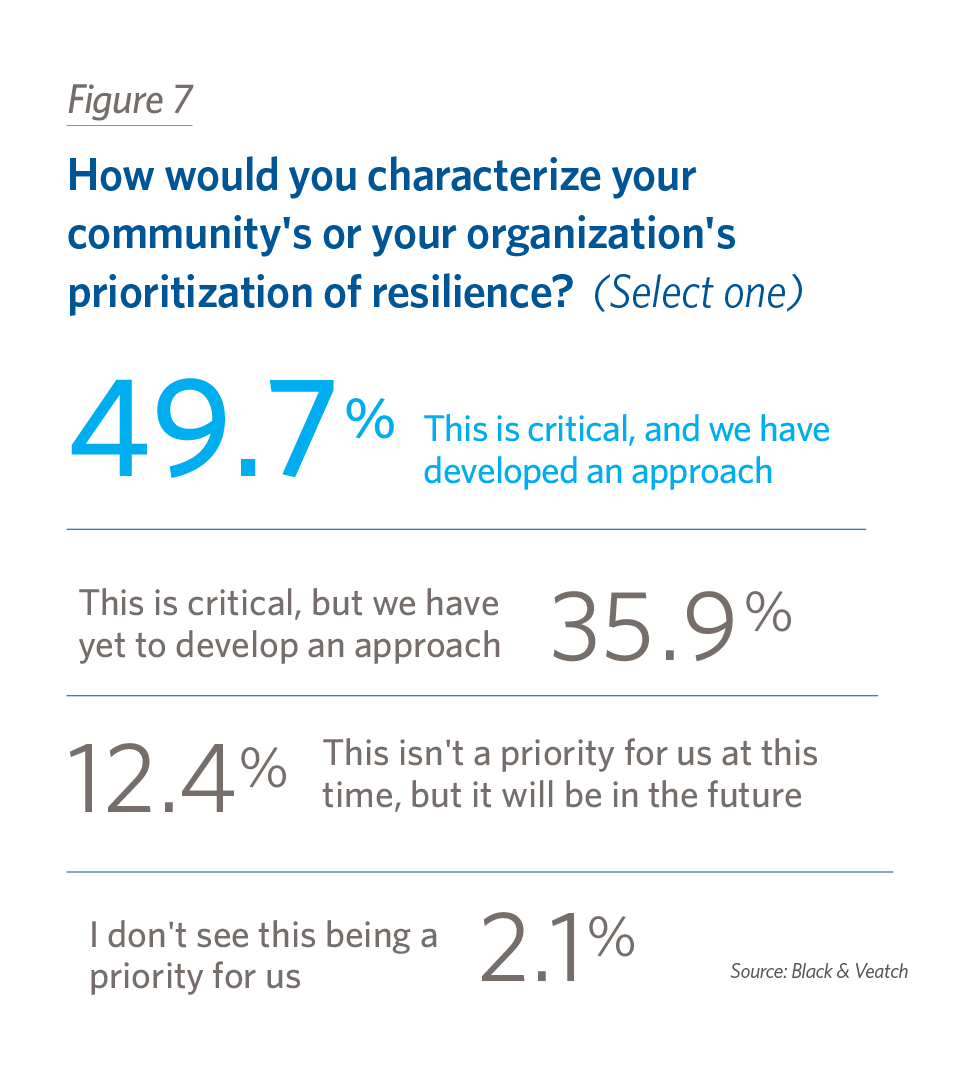

Resilience refers to a water system's ability to rebound after an event. Extreme drought is part of it, but so is flooding, contamination, cybersecurity and more. Among the 430 respondents who participated in the survey, 86 percent rate resilience a crucial priority for their community. Unfortunately, only half of them say their organization has developed an approach to address this issue. More than a third (36 percent) say resilience is crucial, but their team has yet to make formal plans for achieving it. Another 12 percent see resilience becoming important in the future.

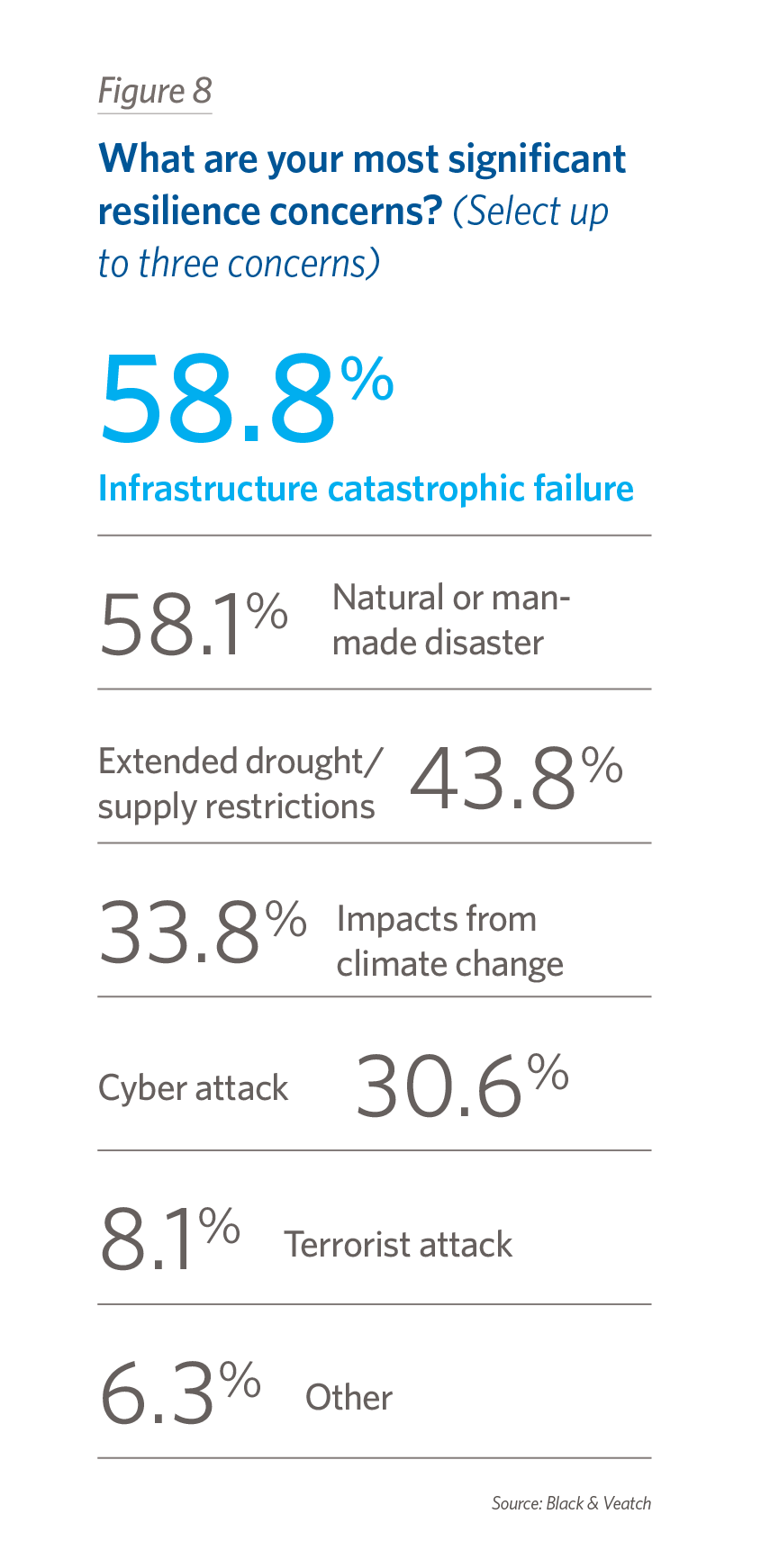

Multiple threats keep water providers up at night, and catastrophic infrastructure failure tops the list. Fifty-nine percent named it as a significant concern, and 58 percent said the same about natural or manmade disasters. Weather-related threats also were high on the list, as 44 percent named drought as a worry, and 34 percent have climate-change impacts in their sights.

Such awareness prompts new approaches to system operation. one utility on Florida's eastern coast is anticipating sea-level rise. The organization's leaders are incorporating 100-year storm surge events into plans for wastewater treatment plant upgrades, and they're engineering all the electrical components to sit 25 feet above land surface.

Even without storm surges, seawater intrusion is negatively impacting groundwater in Florida as aquifers are pumped more than they're recharged. Some utilities are looking at injecting reuse water into aquifers to form saline barriers.

Across the United States, states are seeing more intense flood events and droughts. There's enough water today, but climate variability brings the potential for increased scarcity and reduced reliability. What's more, new development is likely to be costly, time-consuming, or both, regardless of whether it's destination, reuse technology, new reservoirs or well field development. The low-hanging fruit is gone.

Ahead, utilities may look to increasingly recharge efforts to secure safe yield in aquifers, adding water storage and adding water supply to boost climate change resilience and mitigate vulnerability.

Best-Laid Plans

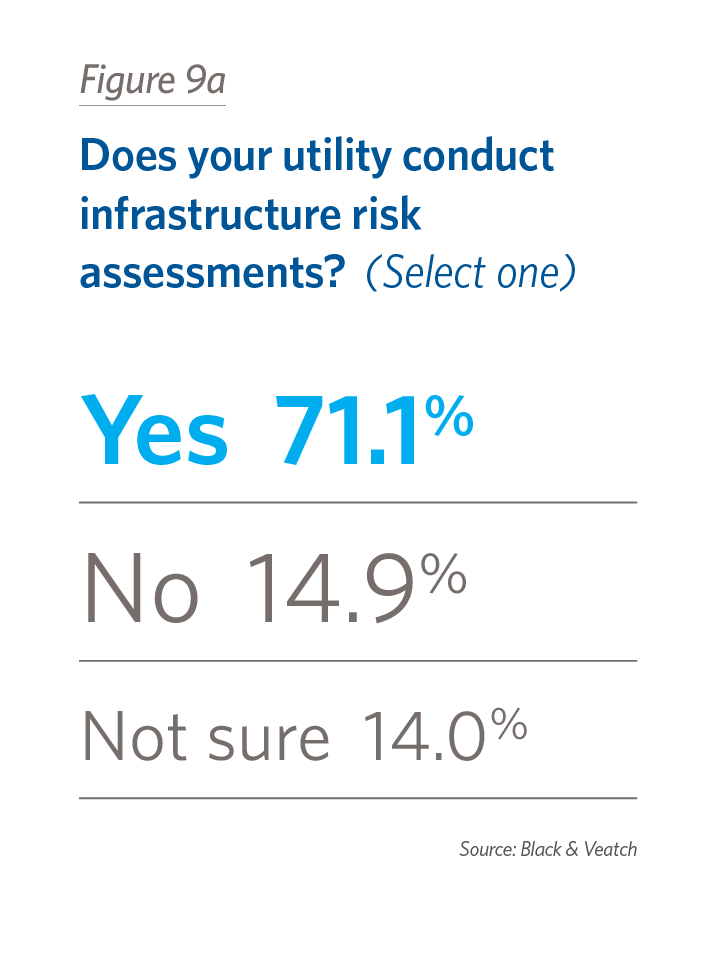

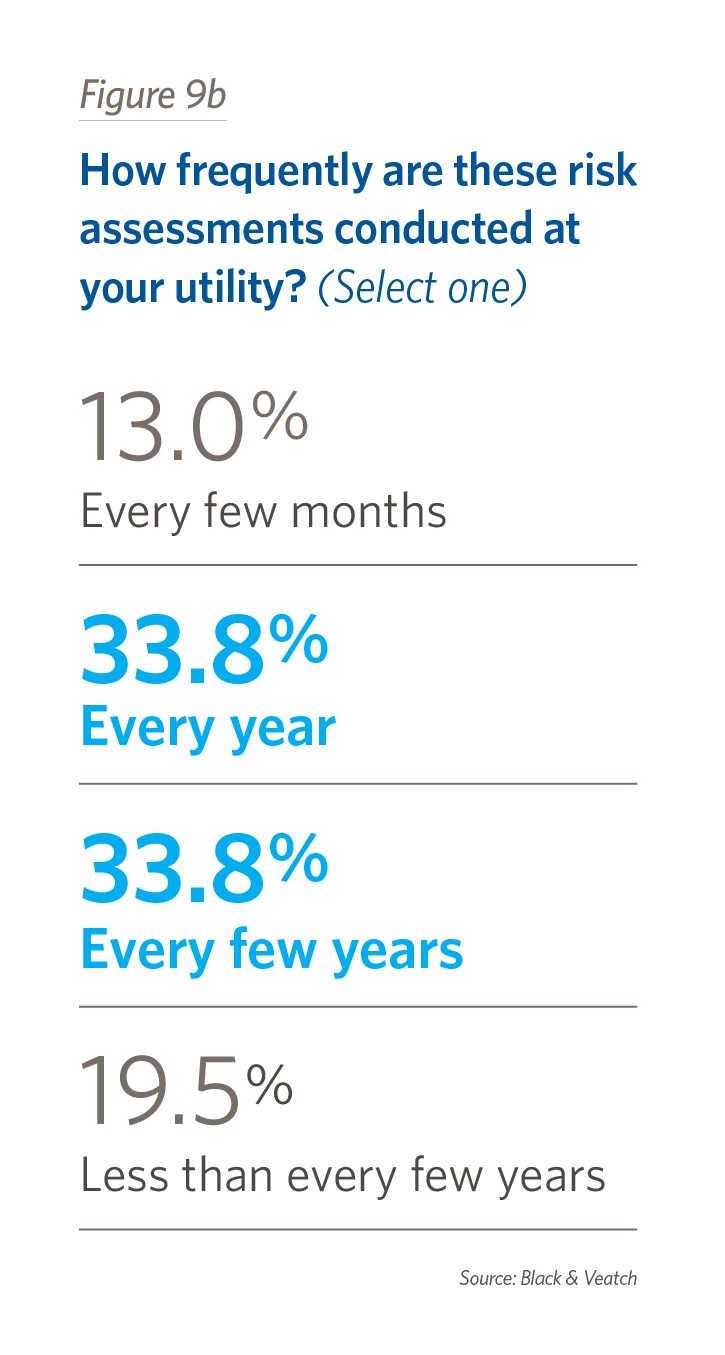

A bright spot in survey results in that 71 percent of respondents work for organizations that conduct infrastructure risk assessments. Four out of five wisely perform these exercises at least every few years.

Fifteen percent conduct no risk assessments at all. Master plans formerly focused on simple hydraulic monitoring and forecasting. Today, utilities can use these exercises to evaluate the big picture.

This means looking at every step in the water delivery process. If the organization runs an integrated model – water, wastewater, stormwater, reclaimed water – staff should be examining the whole water journey: how they get the water to the plant, to the customers, to the wastewater plant, back into the reclaim and, eventually, back into the environment or, if appropriate, back into the water system itself.

Organization staff should look for risks to their infrastructure and balance those risks against the criticality of the assets. Is it a crucial piece of infrastructure – such as a water main that is the only source of water for an area – or is it something that can be quickly replaced, such as a pump with a backup device in a warehouse? What is the likelihood and consequence of failure? How can redundancy be built into the system? These are the kinds of questions water providers should be answering at least once every five years.

When it comes to the hazards for which survey respondents plan, 90 percent look for ways to mitigate infrastructure failure, and 68 percent evaluate risks associated with physical security, such as terrorism or wildfires. nearly 60 percent chart cybersecurity threats, with one-third of respondents planning for recovery after an attack on infrastructure.

More than four of every 10 respondents (42 percent) budget more toward maintenance, and 25 percent split their dollars between maintenance and new infrastructure. Only 17 percent are slanting budgets toward new infrastructure investments, and 16 percent invest with little or no pattern.

Securing the Future

Water providers do try to be proactive with their investment. Unexpected events and – at times – political pressure can sidetrack such foresight. Still, most utilities could likely benefit from an investment strategy that is more proactive than reactive.

In its "Report Card for America's Infrastructure," the American Society for Civil Engineers (ASCE) gives the nation's drinking water infrastructure as a disturbing grade of "D," and has for some time. The nation's wastewater grade recently went up – now it earns a "D+."

According to ASCE, the nation's drinking water travels to customer premises via approximately 1 million miles of pipes, many of which have a lifespan of only 100 years but were installed in the early to mid-20th century. ASCE also notes that, utilities have an average replacement rate of 0.5 percent of their pipes each year, which means it will take some 200 years to turn over the whole system.

While Black & Veatch's 2019 Strategic Directions: Water Report survey results show that most utilities are planning for maintenance of their systems, being more proactive with their systems would be more cost-efficient. Yes, it will cost more upfront, but investments in new infrastructure will pay off.

Utilities may be foregoing this type of investment because they don't have the funds. Nearly two-thirds said their organization doesn't have a steady funding source for resilience from the state or federal level.

There are, in fact, multiple funding resources available through state and federal agencies, and more funding is coming through the America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (AWIA 2018). It reauthorized the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act, legislation that establishes a water infrastructure bank under the U.S. Environment Protection Agency to support water systems through low-interest, long-term loans and loan guarantees for a variety of water projects.

Money also is available through the Drinking Wate State Revolving Fund program, a 1996 amendment to the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act, which so far has provided $35.38 billion in assistance to water systems for 14,090.

Given that AWIA 2018 also calls for utilities to have emergency response plans and risk assessments, now would be a good time for utilities to start writing those grant requests. After all, restoring aging infrastructure, accommodating weather variability and expanding water systems to keep up with population growth is going to take plenty of work.

How much might that work cost? The American Water Works Association puts the price tag at $1 trillion through 2035.

Clearly, resilience will continue to be a pressing need faced by U.S. water utilities for years to come. Rain or shine, it's time to meet the challenge.