Understanding Shared Value

The Evolution of Value Series - Part 9, by Wayne Visser

Another reframing of value was introduced by Harvard professor Michael Porter and management consultant Mark Kramer in Harvard Business Review in 2011.[i] Noting that “the capitalist system is under siege” and that “in recent years business has increasingly been viewed as a major cause of social, environmental, and economic problems”, Porter and Kramer proposed creating shared value as a solution. They were at pains to point out that shared value “is not social responsibility, philanthropy, or even sustainability, but a new way to achieve economic success.”

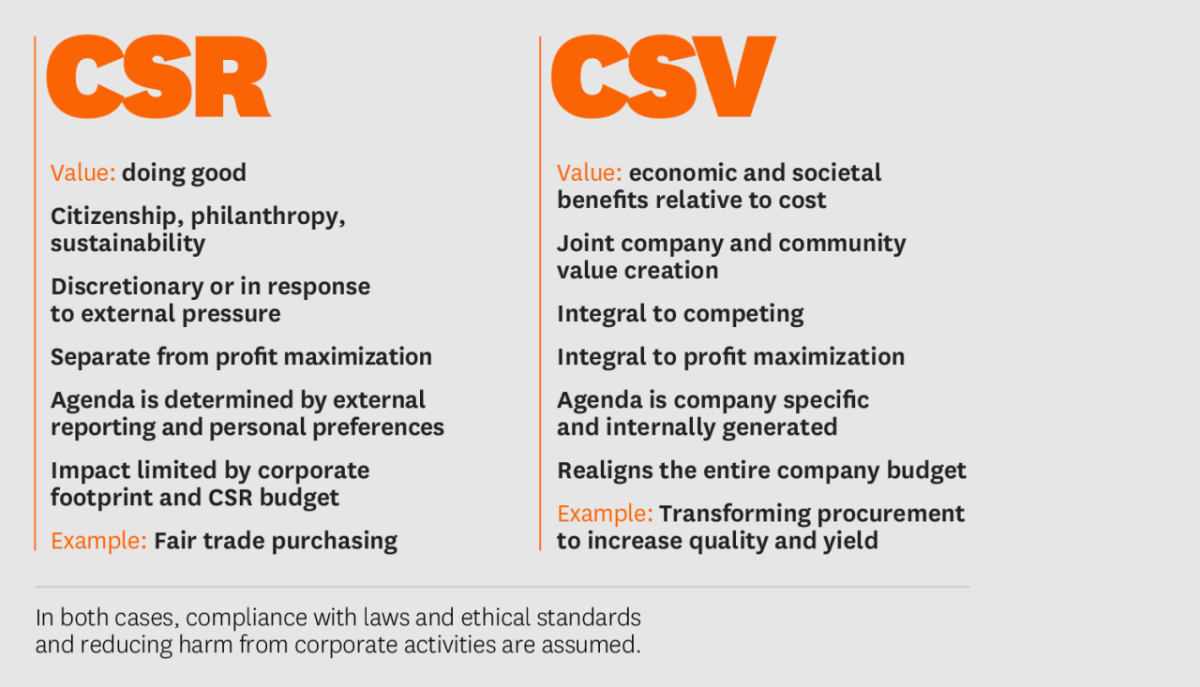

The basic idea is to reconnect company success with social progress. More specifically, shared value includes “policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates.” The example Porter and Kramer cite is investing in the productivity of farmers in the supply chain. The outcome is better for the farmers and better for the company. They contrast this shared value approach with CSR, which they perceive as philanthropy, and fairtrade, which they characterise as simply paying a fairer price for farmers’ produce.

Shared value proposes three main strategic reorientations: 1) Re-conceiving products and markets by seeking out social problems where serving consumers and contributing to the common good might be achieved in parallel; 2) Redefining productivity in the value chain by simultaneously enhancing the social, environmental, and economic capabilities of supply chain members; and 3) Enabling local cluster development so that various developmental goals can be achieved in cooperation with suppliers and local institutions.

Shared value has not been without its vehement critics, mostly from other academics. The first criticism is that the concept is not new or unique. At the very least, we can say that it strongly echoes the work of C.K. Prahalad and Stuart Hart on inclusive business, Jed Emerson on blended value and earlier scholars on corporate social responsibility and corporate social performance. Unfortunately, apparently due to Harvard Business Review’s style guidelines, Porter and Kramer did not acknowledge any of the work that preceded theirs. As a result, Hart on one occasion accused them of intellectual piracy.

A second criticism is that the way they characterise CSR and fairtrade are outdated and frankly inaccurate. ISO 26000, published in 2010, describes social responsibility as a holistic practice that goes beyond its philanthropic roots, covering seven core subjects (human rights, labour rights, environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues, organisational governance and community involvement and development). Similarly, besides offering farmers a better price for their produce, the fairtrade movement has been promoting improved seed varieties and delivering training to enhance farmer skills and improve crop yields for years.

Despite these criticisms, we must give Porter and Kramer their due. Shared value injected a new energy into the debate about the role of business in society. It cleverly changed the language of social responsibility into the language of value creation, which business leaders can better understand, and it has challenged the narrow definition of corporate purpose to go beyond profit maximisation. The result has been a better alignment between companies’ core strategy and the social problems that it can have an impact on.

The concept has also not stood still, as Kramer elaborated in our AMS-ABIS Value Creation Roundtable. Some of that evolutionary work has been on the “ecosystem of shared value,” as he describes in an article with Marc Pfitzer on the subject.[ii] The collective impact movement that has facilitated successful collaborations in the social sector can guide businesses in bringing together the various actors in their ecosystems (such as governments, NGOs, companies and community members) to help remedy some of the world’s most urgent problems.

In order to create shared value through this collective-impact approach, Kramer and Pfitzer suggest that five elements must be in place: (1) a common agenda, which helps align the players’ efforts and defines their commitment; (2) a shared measurement system; (3) mutually reinforcing activities; (4) constant communication, which builds trust and ensures mutual objectives; and (5) dedicated “backbone” support, delivered by a separate, independently funded staff, which builds public will, advances policy, and mobilises resources.

One of the adopters of shared value is Nestlé, which believes it “is about ensuring long-term, sustainable value creation for shareholders while tackling societal issues at the same time.” They express their commitment to shared value in three interconnected impact areas – individuals and families, communities and the planet – which allow them to fulfil their purpose “to unlock the power of food to enhance quality of life for everyone, today and for generations to come.” These translate into long term shared value ambitions: for individuals and families, to help 50 million children lead healthier lives; for communities, to improve 30 million livelihoods in communities directly connected to our business activities; and for the planet, to strive for zero environmental impact in our operations.

[i] Porter, M.E. & Kramer, M.R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89(1): 2-17.

[ii] Kramer, M.R. & Pfitzer, M.W. (2016). The ecosystem of shared value. Harvard Business Review, October.