What a Nobel Prize-Winning Scientist Taught These Two 3Mers

Originally published on 3M News Center

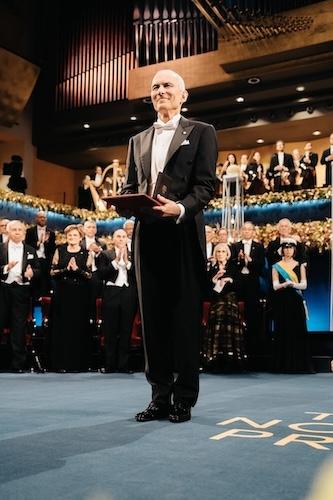

On Dec. 10, 2023, Dr. Moungi Bawendi stood on stage in Stockholm and was awarded — along with Professor Louis E. Brus and Dr. Aleksey Yekimov — the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery and synthesis of quantum dots. Surrounded by grandeur and in the presence of the King and Queen of Sweden, Dr. Bawendi gave a speech and first acknowledged the students, postdoctoral fellows and collaborators who contributed to their work.

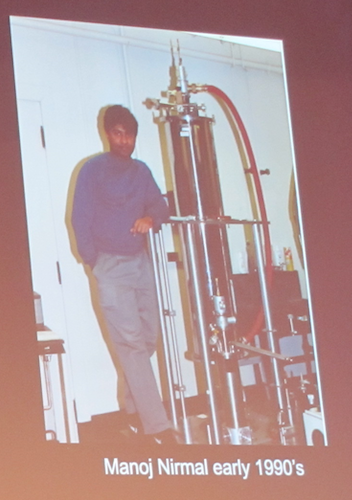

This group includes two current 3Mers: Manoj Nirmal and Catherine Leatherdale. Manoj is a product developer in the Consumer Business Group Lab, and Catherine is a lead data scientist specialist in the Transportation and Electronics Business Group Lab.

Although Manoj and Catherine worked with Dr. Bawendi at different points in his career, the esteemed scientist’s caring nature and respect for scientific integrity made a lasting impression on both of them.

The early years

Manoj was one of Dr. Bawendi’s first students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1990. As a first-year, non-tenured assistant professor, Dr. Bawendi had a lot to prove.

“He was [at the lab] seven days a week,” Manoj said. “We could look and see Sunday at 7 p.m., his light was on.”

Dr. Bawendi came to MIT with an ambitious proposal, building on his previous work at Bell Labs and the work of other scientists. Quantum dots — tiny semiconductor particles that emit different colors based on their size — had already been discovered. However, the methods to synthesize the particles were limited in the size and quality of particles. Well defined, different size particles were critical in the search to understand how properties like color change with size.

Manoj and the two other students worked alongside Dr. Bawendi, who provided hands-on training in all aspects. And his care and compassion for others went beyond his students. Manoj recalled a time Dr. Bawendi paused their conversation after spotting a child walking past the lab. With helium on hand — which the lab used to cool quantum dot samples down to cryogenic temperatures — he quickly found a balloon and filled it for the child.

Among many similar moments of levity, the team worked incredibly hard. Within two years, they made a breakthrough: hot-injection synthesis, a method for making quantum dots that are high quality and a consistent, defined size.

“Once we had the material, we could work with our theoretician collaborator and study all those properties,” Manoj explained. “It was this beautiful demonstration of agreement between theory and experiment.”

Lessons learned

In 1995, after the synthesis of quantum dots, Catherine chose Dr. Bawendi as her Ph.D. advisor when she attended MIT. At this point, researchers could create quantum dots very uniformly, assemble them like artificial atoms and make new materials from those atoms (called a quantum solid). Catherine studied the electrical properties of quantum solids.

Further along in his research, Dr. Bawendi was more hands-off with his students, but his encouragement was palpable. While he wasn’t going to solve a problem for a student, he was there to help when needed.

“I remember one particular instance, there was a very temperamental laser in the spectroscopy lab, and I had spent two solid weeks trying to make this thing lase. I was at the end of my rope and I think he could see as much,” Catherine recalled. “He came down that afternoon and in about 30 minutes he had the thing going again.”

In addition to teaching his students to “stand on their own two feet,” as Catherine put it, Dr. Bawendi emphasized scientific integrity. After synthesizing quantum dots, the students were eager to publish — a common impulse in the characteristically competitive scientific community. But Dr. Bawendi insisted the team continue working to ensure they got it right and didn’t compromise on standards.

“It’s more important to be high quality and get it right than to be first,” Manoj remembered Dr. Bawendi saying. “And that’s something that I’m sure both Catherine and I bring with us even to this day.”

Catherine agreed: “He taught you to follow your intuition, too, and your gut can be right, but you’ve got to fill in all the steps.”

Advancing nanotechnology

On the morning of Oct. 4, 2023, Catherine was reading the Minnesota Public Radio News app and Manoj was reading The New York Times when they learned Dr. Bawendi won a share of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Both insisted it was only a matter of time.

After hearing the news, Manoj called Dr. Bawendi’s admin at MIT and left a message congratulating his former teacher. To his surprise, Dr. Bawendi returned the call later that day, thanking Manoj for taking a chance on a young, first-time professor at MIT. A few months later, Manoj traveled to Stockholm and attended Dr. Bawendi’s Nobel Prize lecture.

Today, quantum dots are used in biomedicine, photovoltaics (solar panels), computer screens and TVs, among many other commercial products.

“Any time you walk into a Best Buy or a Costco and you see a Samsung TV and a good one, there’s a pretty good chance that — if it says QLED — it’s these materials,” Manoj pointed out. “[Quantum dots have] enabled a multi-billion-dollar industry.”